Friday, November 30, 2007

The critical thinking/debate bloc from the High School came to the woodshop today to work on their cube puzzles based on the website. My job in preparation was to cut hundreds of small cubes of walnut, cherry and maple. The students had to sand each block and then design their puzzles. Some finished a first one today. We will have finished puzzles to show next week. The students and teacher all seemed to enjoy the woodshop today as a diversion from more intensive study. Teacher Pete chose a particularly hard puzzle and then spent most of the class trying to put it together. I tried the same one and glued a part backwards so there was no way for it to ever work. I'll try again next week. This is a particularly fun project for kids, but has a valuable hidden purpose called spatial visualization, or spatial sense. Development of spatial sense is a necessary component to success is algebra and geometry as described by the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics (NCTM) in their publication of educational Standards.

Saturday, December 1 has been declared "Buy Local Day" in Eureka Springs. The idea is two-fold.

First, by buying locally made products, we reduce transportation costs and the severe impact of transportation on our environment. No long trips to the mall on Saturday! And no long trips of stuff from China or wherever in ships and trucks, bringing us bad with the goods.

The second part of the idea is that by buying locally, we keep wonderful creative capacity in our own community and encourage our neighbors both morally and economically in responsible and productive citizenship.

(Question! Would we rather have cities filled with pan-handlers or artisans? We get to choose.)

While it is unlikely that the world's citizenry will put aside its fascination with all that is new and different -- the exotic goods that comes from far away places -- it is good to open our eyes to home, its many pleasures and resources, and it is good to open our pockets to reward the creativity and responsibility of our neighbors.

I was invited to a dinner meeting last night of Leadership Arkansas. It is a great program sponsored by the Arkansas State Chamber of Commerce, and the current leadership class was meeting in Eureka Springs to study the tourist business and its impact on the state. Last night I was honored when director/president Paul Harvel introduced me to the large audience and then presented eight of my small boxes to those who had worked hard to prepare for the conference here in Eureka Springs. Paul had told me some years ago of his loyalty to Arkansas, a thing expressed in word and deed through his commitment to the purchase and use of Arkansas products. My own craftsmanship and my own growth as an artist has been the result of support by Paul and others whose hearts have been wide open to the concept of buying local.

So, celebrate with us wherever you are tomorrow. Buy something or make something that means something. Open your eyes to the wonders of your own community.

First, by buying locally made products, we reduce transportation costs and the severe impact of transportation on our environment. No long trips to the mall on Saturday! And no long trips of stuff from China or wherever in ships and trucks, bringing us bad with the goods.

The second part of the idea is that by buying locally, we keep wonderful creative capacity in our own community and encourage our neighbors both morally and economically in responsible and productive citizenship.

(Question! Would we rather have cities filled with pan-handlers or artisans? We get to choose.)

While it is unlikely that the world's citizenry will put aside its fascination with all that is new and different -- the exotic goods that comes from far away places -- it is good to open our eyes to home, its many pleasures and resources, and it is good to open our pockets to reward the creativity and responsibility of our neighbors.

I was invited to a dinner meeting last night of Leadership Arkansas. It is a great program sponsored by the Arkansas State Chamber of Commerce, and the current leadership class was meeting in Eureka Springs to study the tourist business and its impact on the state. Last night I was honored when director/president Paul Harvel introduced me to the large audience and then presented eight of my small boxes to those who had worked hard to prepare for the conference here in Eureka Springs. Paul had told me some years ago of his loyalty to Arkansas, a thing expressed in word and deed through his commitment to the purchase and use of Arkansas products. My own craftsmanship and my own growth as an artist has been the result of support by Paul and others whose hearts have been wide open to the concept of buying local.

So, celebrate with us wherever you are tomorrow. Buy something or make something that means something. Open your eyes to the wonders of your own community.

Thursday, November 29, 2007

I had a very busy morning in the Clear Spring School woodshop, preparing materials for lessons. the short story class in high school is making book racks for the books they are reading, so this afternoon we met to cut the mortises in the quartersawn white oak ends. Tomorrow morning the rest of the high school students who are studying critical thinking and debate will make 3 x 3 cubic block puzzles as shown at www.johnrausch.com. I cut up small 7/8" cubes of walnut, cherry and maple and the students can choose which of several puzzles to construct. Tomorrow I'll have photos. The puzzle cubes are easy to make. I planed down material to 7/8" thick, joined the edges straight and then ripped them into 15/16" strips. After planing the stock to 7/8" thickness in both dimensions, I used a sled and stop block on a table saw to cut the cubes to exact lengths. Tomorrow the students will sand their blocks, arrange them into an interesting patterned cube, then select the parts, tape them together and glue them into various shapes.

One of the challenges faced by those want to provide more hands-on activities in schools, is what do we call it? What name do we give to what we do? At one time, the word "Sloyd" was used to describe craft activities that had educational purposes beyond simply providing training in a trade. But for many in the United States, adhering to a formal set of models was perceived as too rigid and was believed to stifle creativity. So, educators came up with the term manual arts, manual training and industrial arts, each obscuring rather than clarifying the core mission of crafts in schools. Even now, in "career and technical education," or CTE some teachers may be on the cutting edge of technology, using computer driven CNC routers to attempt to educate their students in modern manufacturing techniques, while other teachers may be on the cutting edge in another way entirely, using hand tools to teach skills, attention and sensitivity to materials involving the human emotional content of work that computers will never replace.

Here is how Charles A. Bennett addressed the issue, showing that even as early as 1917, clarity of mission was a confusing thing for woodshops:

Here is how Charles A. Bennett addressed the issue, showing that even as early as 1917, clarity of mission was a confusing thing for woodshops:

While the term "industrial arts" was first used to designate work that developed as a reaction against the formalized courses inherited from Froebel (Sloyd), the term has become so popular in the United States of America that it is coming to include all instruction in handicrafts for general education purposes whether formalized or not. Its meaning is essentially the same as the term "manual arts," though its connotations are different. In the term industrial arts the "industrial" is emphasized; while, in manual arts, the "arts" is historically the distinctive word and in the term manual training "manual" is the important word.Part of the mission of this blog is to discuss and create a clearer vision of what we are doing, and how we can best serve our children and their futures. It is very difficult to come up with clear terminology that can be widely shared and understood and that clarifies our mission, and when the mission isn't clear, the results are obvious. We see school woodshops close and the tools sold on eBay to make room for yet another computer lab to teach skills for jobs soon to be exported to wherever cheap labor can be connected to a T-1 line. But the pendulum swings. As we gain clear vision and restored mission, we will return to the wisdom of the hands.

Wednesday, November 28, 2007

The following is from Charles A. Bennett's History of Manual and Industrial Education from 1870-1917:

...John Dewey's School and Society in 1899 (placed) industrial occupations at the very center of the elementary school curriculum. He accepted the idea that manual training in the lower grades of the elementary school, at least, should be regarded as a method of teaching--as a means of teaching related subject matter--but in these grades he would make the industrial occupations so broad and rich in related content that they would very readily and naturally become the basis for instruction in the so-called other subjects. Moreover, he would not select occupations that were merely typical of adult life, but, occupations that were real in school life. They should serve as "instrumentalities through which the school itself shall be made a genuine form of community life, instead of a place set apart in which to learn lessons."As Dewey later described:

A large part of the educational waste comes from the attempt to build a superstructure of knowledge without a solid foundation in the child's relation to his social environment. In the language of correlation, it is not science, history, or geography that is the center, but the group of social activities growing out of the home relations. It is beginning with the motor rather than with the sensory side... It is one of the great mistakes of education to make reading and writing constitute the bulk of the school work the first two years. The true way is to teach them incidentally as the outgrowth of the social activities at this time.As further explained by Bennett:

With this new philosophy put into practice, all teachers needed to be taught the arts and crafts, industries and occupations, that were serviceable in the home, school and play environments of children.

Today in the Clear Spring School woodshop, the 5th and 6th grade students finished carving and sanding pens and then began making toy cars and trucks for free distribution to children through the local food bank. Killian drilled holes in wheels while other students sawed and sanded the bodies of their cars. Reflection after class led to a lively discussion of recent news about the recall of Chinese toys, the few things that can be bought this year that are "Made in America," and the actual pleasure we can find in making things on our own.

Today in the Clear Spring School woodshop, the 5th and 6th grade students finished carving and sanding pens and then began making toy cars and trucks for free distribution to children through the local food bank. Killian drilled holes in wheels while other students sawed and sanded the bodies of their cars. Reflection after class led to a lively discussion of recent news about the recall of Chinese toys, the few things that can be bought this year that are "Made in America," and the actual pleasure we can find in making things on our own.

Here in the US, as reported in the Dec. 3 issue of Time Magazine, "Anxious parents are trying to give their kids and academic edge before they get to kindergarten." So they are paying small fortunes to tutor their toddlers. But this fad is counter productive according to most child development experts. Recent brain-imaging data shows that most children aren't ready to read until 5 at the earliest, and a recent study shows that graduates of academically intensive pre-schools are less creative than children graduating from regular play based pre-school programs. As stated by David Elkind author of The Harried Child, "Kids already learn what they need to know in a traditional learning-through-play program."

When it comes to child development, a wise parent knows the value of the saying, "Don't push the river." Or as we have been known to say in Arkansas, "You can't push a rope." Smart parents would choose instead to live lives that set an example of engagement and creativity, knowing their own children will accept the challenge and the encouragement they offer at the time it best matches their own natural development. But, hey. We are a nation of idiots, right?

When it comes to child development, a wise parent knows the value of the saying, "Don't push the river." Or as we have been known to say in Arkansas, "You can't push a rope." Smart parents would choose instead to live lives that set an example of engagement and creativity, knowing their own children will accept the challenge and the encouragement they offer at the time it best matches their own natural development. But, hey. We are a nation of idiots, right?

Tuesday, November 27, 2007

As shown in the photo at left, we began making pick-up truck stamp and paper clip dispensers in the 3rd and 4th grades as a economics project. Today each student worked on their own start to finish and next week we try division of labor and create an assembly line. The photo below shows the 1st and 2nd grade students with the friendship boxes they finished in today's woodshop. They will start on star shaped Christmas ornaments next week.

As shown in the photo at left, we began making pick-up truck stamp and paper clip dispensers in the 3rd and 4th grades as a economics project. Today each student worked on their own start to finish and next week we try division of labor and create an assembly line. The photo below shows the 1st and 2nd grade students with the friendship boxes they finished in today's woodshop. They will start on star shaped Christmas ornaments next week.

Today the 3rd and 4th grade students at Clear Spring School begin their study of economics. This is the repeat of a project we did two years ago and that was described in Woodcraft Magazine last year. The project involves the making of toy cars that also serve as a stamp and paper clip dispensers. The first week, they make one for their own use as practice. The second week we set up an assembly line so the toy cars can be manufactured Henry Ford style. In the meantime, the students analyze the product's components in the economic terms "land labor and capital," determine price, develop sales literature and then sell them to raise money for their trip to Springfield, Missouri later in the spring. It is a fun project. The 1st and second grade students will finish their friendship boxes today. The photo above is from 2 years ago. Current photos will come later in the day.

Monday, November 26, 2007

A friend of mine Elliot Washor, just returned from Australia where he had a couple meetings with Mark Thomson, who wrote: "Rare Trades, Makers, Breakers and Fixers" and "Blokes and Sheds". Those are books I know I'll have to look into, and perhaps some of my Australian readers will fill us in.

Earlier in the year, I told here in the blog about my visit to Mora, Sweden at prom time, when there were hundreds of American cars on the street. You can find out about this if you use the search function at the top left of the page. When I was in Little Rock with friends last week, they told me about meeting a couple young Swedish men traveling on a great American road-trip in an old American car that they had purchased on eBay. They had to spend more time than expected in Chicago doing needed repairs, but barring further breakdowns are probably home in Sweden now, ready for a long winter restoring it to perfection in time for the spring thaw and prom night. There is a code hard wired in the human genome that says: take apart and fix or make.

Earlier in the year, I told here in the blog about my visit to Mora, Sweden at prom time, when there were hundreds of American cars on the street. You can find out about this if you use the search function at the top left of the page. When I was in Little Rock with friends last week, they told me about meeting a couple young Swedish men traveling on a great American road-trip in an old American car that they had purchased on eBay. They had to spend more time than expected in Chicago doing needed repairs, but barring further breakdowns are probably home in Sweden now, ready for a long winter restoring it to perfection in time for the spring thaw and prom night. There is a code hard wired in the human genome that says: take apart and fix or make.

The following is a brief note for the Clear Spring School Newsletter.

The following is a brief note for the Clear Spring School Newsletter. In order to fully understand the woodworking program at Clear Spring School you have to go back to the late 1870s. When the manual arts were first introduced to schools in the US by Calvin Woodward at Washington University and John D. Runkle at MIT, it was because these early educators had noticed deficiencies in their engineering students. These students needed hands-on experience in 3 dimensional reality to be qualified for the intellectual components of their work. In those early days, the connection between the hands and the brain in learning was widely accepted as an educational concept.

However, during much of the 20th century, using modern manufacturing as their model, educators sought greater efficiency and economy in the processing of students through the system. This meant large numbers of students in the classroom, with material being delivered by lecture, often missed or ignored by students whose hands were now to be stilled and neatly folded on their desks. It also meant a division in schools, separating the work of the hands from the work of the intellect as described by Woodrow Wilson when he was President of Princeton.

"We want one class of persons to have a liberal education, and we want another class of persons, a very much larger class, of necessity, in every society, to forgo the privileges of a liberal education and fit themselves to perform specific difficult manual tasks."

When he became President of the US, Wilson pushed the Smith Hughes Act through Congress simultaneously providing certain schools with money for technical education and stripping academic institutions of the challenge and responsibility of providing hands-on experience.

The Wisdom of the Hands program was founded on the recognition that the engagement of the hands is an essential element in the engagement of the intellect and the realization of its full capacities for all students, including those who choose to pursue academic careers.

It is interesting that now, at last, modern scientific methods are proving the hand/brain system that had been widely observed and understood by early educators and largely ignored in recent decades. Some of the research that is most convincing involves the use of gesture in the teaching of math as described in a Washington Post article in August 2007 Gestures Convey Message: Learning in Progress

Researchers at the University of Chicago, University of Rochester and other top research universities are finding the use of the hands in gesture to be a clear view into the workings of the mind as it processes information and as we learn. Most simply stated, the movement of the hands facilitates the movement of thought in the brain, and as we use our hands in learning we become more intelligent as well as more creative.

So, when your children bring home objects from the woodshop, bent nails and all, please know that it is not just the hand that is being trained and encouraged, but the mind as well. When they come home talking about saws and knives, please note that Clear Spring School and your child are at the cutting edge of education.

Sunday, November 25, 2007

John Grossbohlin sent photos of his son Joshua resawing walnut sides for a chess box as shown at left. At the show, I had a chance to visit with Laura Waters, art teacher from the Rogers School District. She is involved in her second year using woodworking inspired by the Wisdom of the Hands program in her arts curriculum. I finished my craft show, made a little money, and talked with a few friends about our hands. But it is always a relief to get done, pack up, and go home ready for another day in the woodshop. Tomorrow I prepare materials for Tuesday's classes.

John Grossbohlin sent photos of his son Joshua resawing walnut sides for a chess box as shown at left. At the show, I had a chance to visit with Laura Waters, art teacher from the Rogers School District. She is involved in her second year using woodworking inspired by the Wisdom of the Hands program in her arts curriculum. I finished my craft show, made a little money, and talked with a few friends about our hands. But it is always a relief to get done, pack up, and go home ready for another day in the woodshop. Tomorrow I prepare materials for Tuesday's classes.

I am here at the craft show and the images at left show my booth and products. The whole show is full of wonderfully crafted objects. My wife was telling me this morning about a new diet in which you only eat things that come from a radius of one hundred miles of your own home. What if we had a "hundred mile Christmas?" ...One in which every thing we gave was a a reflection of our own communities and the people who live there? I won't hold my breath. We have a ways to go. As to the hundred mile diet, they don't grow coffee or bananas in Arkansas, but we do have is a huge array of hand crafted items suitable for gifts. Maybe I'll sell a few boxes.

I am here at the craft show and the images at left show my booth and products. The whole show is full of wonderfully crafted objects. My wife was telling me this morning about a new diet in which you only eat things that come from a radius of one hundred miles of your own home. What if we had a "hundred mile Christmas?" ...One in which every thing we gave was a a reflection of our own communities and the people who live there? I won't hold my breath. We have a ways to go. As to the hundred mile diet, they don't grow coffee or bananas in Arkansas, but we do have is a huge array of hand crafted items suitable for gifts. Maybe I'll sell a few boxes.

Saturday, November 24, 2007

I made it though the first day of a two day show. Traffic and sales were slight. Hand crafted objects and art don't have the seasonal buzz that is generated by home electronics. One of the visitors in my booth today showed me photos of Hawaii on his iPhone. We are so quickly captured by bells and whistles and we are so poorly trained in the discovery of deeper meaning.

But when the current crop of iPhones and electronic buzz generating devices take the places reserved for them in landfills and recycling centers, the small boxes I sold today will still be beautiful, reflecting the beauty of the forests and the intentions of their maker.

But when the current crop of iPhones and electronic buzz generating devices take the places reserved for them in landfills and recycling centers, the small boxes I sold today will still be beautiful, reflecting the beauty of the forests and the intentions of their maker.

Only 32 more making days until Christmas. You can avoid the panic at the malls completely this year by making holiday gifts to share with your family and friends. You may say, "Sorry, I have no skill." But where in the world does skill come from? It comes from trying, and everyone is clumsy at first.

They say that if you heat with wood it warms you twice. If you make a gift, it gives three times. The first gift is to you, as you find pleasure in the transformation of materials to conform to your own will. This is where you really get to surprise yourself. The second gift is that part of the object, the intrinsic part, its innermost character that states to its recipient, "I made this just for you as a reflection of my caring for you and our relationship, and this comes directly from my heart to you." If you have chosen to make something useful and beautiful, it gives a third time, a much longer time of practical service, with each and every use reminding of a deep and lasting relationship with you.

Would you rather spend time fighting crowds at the mall, or would you rather expand your own life in a much more meaningful direction? Oh, yes, don't forget to turn off the TV while you work. Allow the full depth of your care and attention to enter the work you do. Can you imagine a gift where the full attention of the maker was applied directly to the making of the work? It is better than art, it is called craftsmanship.

They say that if you heat with wood it warms you twice. If you make a gift, it gives three times. The first gift is to you, as you find pleasure in the transformation of materials to conform to your own will. This is where you really get to surprise yourself. The second gift is that part of the object, the intrinsic part, its innermost character that states to its recipient, "I made this just for you as a reflection of my caring for you and our relationship, and this comes directly from my heart to you." If you have chosen to make something useful and beautiful, it gives a third time, a much longer time of practical service, with each and every use reminding of a deep and lasting relationship with you.

Would you rather spend time fighting crowds at the mall, or would you rather expand your own life in a much more meaningful direction? Oh, yes, don't forget to turn off the TV while you work. Allow the full depth of your care and attention to enter the work you do. Can you imagine a gift where the full attention of the maker was applied directly to the making of the work? It is better than art, it is called craftsmanship.

Friday, November 23, 2007

I am all set up at the Fall Art Fair and ready to sell my work. In the meantime, there is an article in this week's Woodshop News about a Philadelphia craftsman, Bernard Henderson shown in the photo at left who moved from a life as a college administrator to the life of a self-employed woodworker. He says:

I am all set up at the Fall Art Fair and ready to sell my work. In the meantime, there is an article in this week's Woodshop News about a Philadelphia craftsman, Bernard Henderson shown in the photo at left who moved from a life as a college administrator to the life of a self-employed woodworker. He says:"We as a body of individuals living in this country, tend to be more enamored with people who don't work with their hands, so the idea that someone would go from a job where they don't work with their hands to another job where they get dirty and the income potential is much lower... what they tend to do is dwell on 'why' you would do that, rather than 'what' it is you do."Also, in the meantime, and in another conversation, John Grossbohlin told me of a hand-cut dovetailed box he had made for a charity auction. A woman bought it for the embarrassing low final bid of $30.00 and then clueless to its real value or the amount of time invested in making it asked if he would make her another for the same price.

Both of these tell the same sad story. We are raising a society that hasn't a clue as to the values of hand-craftsmanship. One end and the other. If people aren't introduced to the pleasure and value of their own creative use of their hands, either in homes or in schools, they will be oblivious to the values of hand-crafted objects and the processes through which they are created. This is the syndrome Neuro-physiologist Matti Bergström in Finland calls "finger-blindness," an impairment preventing a person from being able to perceive the intrinsic value of significant cultural objects or the people who craft them. As I have said before, we have become a nation of idiots, and we will continue thus until we rediscover the wisdom of our hands.

This is Black Friday in the US, and I guess a bit of explanation may be in order for readers in other countries. While black is usually the color of mourning in our culture, Black Friday, the day after Thanksgiving is thought to be a good thing. Its name comes from accounting ledgers in which expenses are marked in red and income in black, and it is thought to be the day in which the pre-holiday buying frenzy pushes the black ledger entries over the top for the year. So we celebrate with huge sales on stuff that will be next season's sacrifice in homage to the gods or goddesses of the land-fills and junk-sales.

Perhaps it should be a day of mourning instead. We have lost the skills and interest in making things ourselves for those we love.

Our lives are driven by ledgers, markings in books, numbers red or black. But our lives can be recorded in other ways. Statistics of the heart and touch, the embrace in pride and joy of things well crafted, useful and beautiful that linger long in our lives. These are objects filled with the energy, emotions and aspirations of their makers.

I have a Black Friday of my own. Today I set up my booth at the Fall Art Fair in Eureka Springs to sell my work on Saturday and Sunday. Friends and neighbors will come. We'll chat. A few may buy small things to give their own families and friends.

Perhaps it should be a day of mourning instead. We have lost the skills and interest in making things ourselves for those we love.

Our lives are driven by ledgers, markings in books, numbers red or black. But our lives can be recorded in other ways. Statistics of the heart and touch, the embrace in pride and joy of things well crafted, useful and beautiful that linger long in our lives. These are objects filled with the energy, emotions and aspirations of their makers.

I have a Black Friday of my own. Today I set up my booth at the Fall Art Fair in Eureka Springs to sell my work on Saturday and Sunday. Friends and neighbors will come. We'll chat. A few may buy small things to give their own families and friends.

Thursday, November 22, 2007

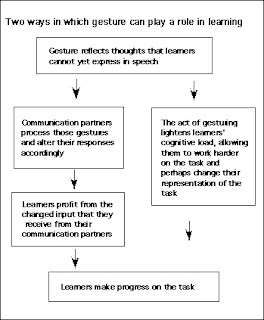

Lightening the cognitive load... A phrase from Susan Goldin-Meadow and Susan Wagner Cook. (see chart below) You might wonder what it means. Use of particular gestures reveals certainty of knowledge and the learner's certainty of the spoken concept. They allow the speaker to put aside those issues that have been previously resolved and move on to unexplored conceptual territory. Actually, the act of doing something of certainty in response to learning is an automatic lightening of load. Take this blog, for instance. When I have written something down and shared it with my readers, it is no longer a cognitive burden, but is recorded and forms the foundation for subsequent exploration. It is what happens when learning leads to responsive action...

In schools, the materials learned are rarely put to practical use. The absorption of materials is measured and monitored in the taking of tests and the writing of papers, but the materials themselves are left untested in direct comparison to fundamental reality. Once the test is taken and the paper is complete, the materials are no longer required, are often forgotten and fail to form the necessary platform for future exploration and growth. So, what can we do about it? Put children to work on real things that have significance in their lives and the lives of their community and family. You will find the hands lifting the cognitive burden, refreshing the thoughts and lifting the spirits.

In schools, the materials learned are rarely put to practical use. The absorption of materials is measured and monitored in the taking of tests and the writing of papers, but the materials themselves are left untested in direct comparison to fundamental reality. Once the test is taken and the paper is complete, the materials are no longer required, are often forgotten and fail to form the necessary platform for future exploration and growth. So, what can we do about it? Put children to work on real things that have significance in their lives and the lives of their community and family. You will find the hands lifting the cognitive burden, refreshing the thoughts and lifting the spirits.

For my readers outside the United States, today is Thanksgiving. All across America, people are working with their hands to prepare a feast to be shared with friends and family. Some are sharpening their knives for carving turkey and ham. Some will use electric carving knives. We'll let that go by. Just for today, who cares. The chart above is from Susan Goldin-Meadow and Susan Wagner Cook's article How our hands help us learn. Today, at dinner tables across America people will be gesturing with their hands. Italian families will gesture a bit more widely and with a bit greater emphasis as their culture allows, but even if you are half-Norwegian like me your hands will be moving in the creation and expression of thought.

For my readers outside the United States, today is Thanksgiving. All across America, people are working with their hands to prepare a feast to be shared with friends and family. Some are sharpening their knives for carving turkey and ham. Some will use electric carving knives. We'll let that go by. Just for today, who cares. The chart above is from Susan Goldin-Meadow and Susan Wagner Cook's article How our hands help us learn. Today, at dinner tables across America people will be gesturing with their hands. Italian families will gesture a bit more widely and with a bit greater emphasis as their culture allows, but even if you are half-Norwegian like me your hands will be moving in the creation and expression of thought.If the simple seemingly purposeless motions of the hands in gesture have been proved of their role in the development of human intellect, just imagine what it can mean to a child (or an adult) to spend time in a woodshop.

Wednesday, November 21, 2007

The following is from How our hands help us learn, by Susan Goldin-Meadow and Susan Wagner Cook:

Gesture is based on a different representational format from speech. Whereas speech is segmented and linear, gesture can convey several pieces of information all at once. At a certain point in acquiring a concept, it might be easier to understand, and to convey, novel information in the visuospatial medium offered by gesture than in the verbal medium offered by speech.The point of this is of course, that the hands, even when they are not engaged in directly shaping materials, are still engaged in the creative shaping of ideas. That is why sitting at desks with hands stilled is a really dumb notion unless your purpose in schooling is to restrain creativity and train students to conformity, lethargy, and compliance. If our purpose was for children to learn, our schools would look more like Froebel Kindergartens with children working with blocks and planting gardens.

Gesture is not specifically acknowledged. As a result, gesture can allow speakers to introduce into their repertoires novel ideas not entirely consistent with their current beliefs, without inviting challenge from a listener--indeed, without inviting challenge from their own self-monitoring systems. Gesture might allow ideas to slip into the system simply because it is not the focus of attention. Once in, those new ideas could catalyze change.

Gesture helps to ground words in the world. Deictic gestures point out objects and actions in space and thus provide a context for the words they accompany. Gestures might, as a result, make it easier to understand words and also to produce them.

Whatever the process, there is ample evidence that the spontaneous gestures we produce when we talk reflect our thoughts -- often thoughts not conveyed in our speech. Moreover, evidence is mounting that gesture goes well beyond reflecting our thoughts, to playing a role in shaping them.

Reality 101... the quick course for beginners. You may have noticed that an agreement on reality is elusive. Whatever you say or believe may be challenged by others whose view might be just a bit askew from your own.

A number of years ago, I was involved with a citizen's group that was trying to get the city of Eureka Springs to pay some attention to the springs for which it was founded in the late 1880s. It was believed then and well into the 1950's by some that the springs had magical healing qualities, but development around the springs and the leakage of sewage lines from homes and businesses soon made the springs unfit for human consumption. In fact, the health department regularly posted the springs as unfit, and local vigilantes concerned with the loss of tourism would take the signs down in the middle of the night to keep the tourists coming (and going) despite serious risks of infectious disease.

So when it came time to build a new treatment plant, those of us in the citizen's group asked that instead of building a much larger plant, we should take care of the necessary line repairs and stop the leaking of sewage into our springs. And of course, the state and federal governments said, "Yes, we know the springs are polluted, but how can you know it is leaking sewage lines that pollute them?"

Such is the way with science and reality. When you are ready to go off the deep end, you can head any direction you choose. The governmental agencies refused to admit that the leaking sewer lines were the cause of contamination until we had invested a quarter of a million dollars in a study, proving what anyone with intelligence beyond that of a moron would have understood and accepted without question.

Time Magazine this last week presented statistics on what people do each day. Sleep 8.5 hours (35%) Watch TV 2.35 hours (15% of time awake). Start adding in the other forms of escape from reality, and you begin to get the picture. The first thing you need to know about reality is that it exists despite all the traditional means used to escape it, and by using our hands in the making of things we have a chance to experience it. Very sadly, woodworking wasn't an activity significant enough for Time Magazine to list in their statistics.

A number of years ago, I was involved with a citizen's group that was trying to get the city of Eureka Springs to pay some attention to the springs for which it was founded in the late 1880s. It was believed then and well into the 1950's by some that the springs had magical healing qualities, but development around the springs and the leakage of sewage lines from homes and businesses soon made the springs unfit for human consumption. In fact, the health department regularly posted the springs as unfit, and local vigilantes concerned with the loss of tourism would take the signs down in the middle of the night to keep the tourists coming (and going) despite serious risks of infectious disease.

So when it came time to build a new treatment plant, those of us in the citizen's group asked that instead of building a much larger plant, we should take care of the necessary line repairs and stop the leaking of sewage into our springs. And of course, the state and federal governments said, "Yes, we know the springs are polluted, but how can you know it is leaking sewage lines that pollute them?"

Such is the way with science and reality. When you are ready to go off the deep end, you can head any direction you choose. The governmental agencies refused to admit that the leaking sewer lines were the cause of contamination until we had invested a quarter of a million dollars in a study, proving what anyone with intelligence beyond that of a moron would have understood and accepted without question.

Time Magazine this last week presented statistics on what people do each day. Sleep 8.5 hours (35%) Watch TV 2.35 hours (15% of time awake). Start adding in the other forms of escape from reality, and you begin to get the picture. The first thing you need to know about reality is that it exists despite all the traditional means used to escape it, and by using our hands in the making of things we have a chance to experience it. Very sadly, woodworking wasn't an activity significant enough for Time Magazine to list in their statistics.

The following is a statement from Susan Wagner Cook:

In essence, the movement of the hands facilitates the movement and development of thought, and to leave the hands stilled is the failing of American education. Once again, I stretch the thinking of Jean Jacques Rousseau: Put a young woman in a woodshop, her hands will will work to the advantage of her brain. She will become a philosopher while thinking herself only a craftsman.

Gestures are pervasive behaviors, yet they are often overlooked, perhaps because they are not as "fancy" as speech. Gestures are not part of a formal code, and their meaning depends on the available context. However, gesture may enable speakers and listeners to capitalize on just these properties. In particular, gesture may allow people to offload some of the cognitive effort required to produce and comprehend complex and abstract representations, perhaps by incorporating situated and embodied representations. This can have effects on speakers' use of working memory, speakers' memory for events, and children's learning of mathematical concepts.As a life-long craftsman, and teacher of manual arts, the current work in examining the role of gesture in communication and thought provides an important layer of evidence that there is so much more going on in our hands, and in the relationship between our hands and brains than modern schooling allows to unfold.

In essence, the movement of the hands facilitates the movement and development of thought, and to leave the hands stilled is the failing of American education. Once again, I stretch the thinking of Jean Jacques Rousseau: Put a young woman in a woodshop, her hands will will work to the advantage of her brain. She will become a philosopher while thinking herself only a craftsman.

Tuesday, November 20, 2007

This is a particularly fun quote from Charles H. Ham's Mind and Hand, 1886 in light of the research linking the hand with the efficacy of thought:

The... extreme conservatism (in schools) is shown by the remark of a prominent educator who opposes the incorporation of manual training in the curriculum of the public schools. He says, "Some even go so far as to regard the fingers as a new avenue to the brain, and think that great pedagogic advantages will be given by the new method, so that boys may make equal attainments in arithmetic, reading and grammar in less time... They (teachers) will still find the eye and ear nearer to the brain than the hand." No assumption could be more false than this, that the eye and the ear are more important organs than the hand because they are located, physically, nearer the brain.

An article in the Washington Post explains the value of gesture in teaching math. According to the article:

Teachers who use gestures as they explain a concept are more successful at getting their ideas across, research has shown. And students who spontaneously gesture as they work through new ideas tend to remember them longer than those who do not move their hands.According to Arthur Glenberg, a gesture researcher at the University of Wisconsin in Madison the old model of the brain doing everything just doesn't work:

"We're not just dealing with zeros and ones. We're biological beings, and we ought to consider how we deal with the real world and take seriously the fact that we have bodies."According to the article, Susan Wagner Cook's latest work shows

Neuroscientists have found, for example, that the part of the brain that controls hand movements is often active when people are doing math problems. "As though you're counting fingers." Glenberg states.

Similarly, parts of the brain responsible for speech are often active when people gesture -- more evidence of the link between language and movement, aside from formal sign language.

...that even abstract gestures can enhance learning. In a classroom, she had some students mimic her sweeping hand motions to emphasize that both sides of an equation must be equal. Other students were simply told to repeat her words: "I want to make one side . . . equal to the other side."

A third group was told to mimic both her movements and words.

Weeks later, the students were quizzed. Those in the two groups that were taught the gestures were three times as likely to solve the equations correctly than were those who had learned only the verbal instructions, she and two colleagues reported in the July 25 issue of the journal Cognition.

Susan Goldin-Meadow at the University of Chicago has a lab named after her there in honor of her ground-breaking work in non-verbal communication, particularly gesture... use of the hands in speech. I've mentioned Susan's work before in the blog but it is good to revisit old notions that are gaining in relevancy each day. From Susan:

In essence, the movement of the hands helps in the movement of thought and the creation and framing of ideas. Even more important, Susan ties gesture to the exploration of new ideas and creativity, which the brain is not yet able to express as language. A simple limerick from Susan's website explains it:

And of course, the great irony is that what hands research is telling us is that the simple observations of educational theorists like Comenius, Pestalozzi and Froebel from the 18th, and 19th centuries were right and that the forced efficiencies of 20th and 21st century education are so ineffective as to damage children's confidence as learners.

“Why must we move our hands when we speak? I suggest that gesturing may help us think - by making it easier to retrieve words, easier to package ideas into words, easier to tie words to the real world. If this is so, gesture may contribute to cognitive growth by easing the learner's cognitive burden and freeing resources for the hard task of learning.

"Moreover, gesture provides an alternate spatial and imagistic route by which ideas can be brought into the learner's cognitive repertoire. That alternative route of expression is less likely to be challenged (or even noticed) than the more explicit and recognized verbal route. Gesture may be more welcoming of fresh ideas than speech and in this way may lead to cognitive change.”

In essence, the movement of the hands helps in the movement of thought and the creation and framing of ideas. Even more important, Susan ties gesture to the exploration of new ideas and creativity, which the brain is not yet able to express as language. A simple limerick from Susan's website explains it:

If your brain doesn't meet high demandsSo hands stilled in classrooms is the dumbest of notions. We have gone off the deep end in American education. Children need to be active, doing art, making things from wood. If a simple gesture can be such a powerful thing, imagine what it means when those gestures are tied together in the physical expression of ideas, the summation of which are useful and beautiful objects that can last a lifetime.

Here's some gestures to loosen your glands.

Put ‘em up in the air,

Shake ‘em like you don't care.

You'll be smarter if you use your _________.

Answer: HANDS

And of course, the great irony is that what hands research is telling us is that the simple observations of educational theorists like Comenius, Pestalozzi and Froebel from the 18th, and 19th centuries were right and that the forced efficiencies of 20th and 21st century education are so ineffective as to damage children's confidence as learners.

Monday, November 19, 2007

Out of touch with reality. Disney World and American education. I was on my way out of town last week to teach in Little Rock, and I pulled up at the gas pump next to a friend Ernie Kilman who is a talented water color artist, and runs Kings River Outfitters, supplying canoe rentals and pick-up service on the Kings River. The Kings is a highly regarded small mouth bass stream, flowing unrestrained against high bluffs, across gravel bars, through long pools and rapids in the midst of beautiful woodlands. Ernie mentioned how many of his customers are out of touch with basic reality. "It is very disturbing" he said, "but funny, too." He told of one customer (an adult male, complete with wife and children) who asked, "So we put the canoe in here, float downstream, and then we get out over there?" pointing to a spot upstream on the river. "No," Ernie replied, "You can take out here, but I'll have to shuttle you and the canoes to a starting point." "You mean it doesn't flow in a circle?" he asked.

I guess he thought it was an amusement ride, but is this what happens in American education?

Woodworking in schools teaches children to be alert, attentive, and inquisitive. It hones the powers of observation and investigation, and develops the intellect. They've pulled real stuff out of the schools and stilled the hand's natural investigations and guess what we get? Dumb. Very dumb.

I guess he thought it was an amusement ride, but is this what happens in American education?

Woodworking in schools teaches children to be alert, attentive, and inquisitive. It hones the powers of observation and investigation, and develops the intellect. They've pulled real stuff out of the schools and stilled the hand's natural investigations and guess what we get? Dumb. Very dumb.

I am back home after a long weekend in Little Rock, teaching at the Applied Design Center in their furniture design program. I taught furniture design the first day, leading the students through an investigation of design, then beginning the making of a walnut coffee table, the top of which can be seen the in the photo above. The second day, I taught box making as shown below. The furniture program at UALR is in its second year, and is gathering momentum. It has a new director, Mia Hall, who grew up in southern Sweden where she studied Sloyd. She came to UALR after graduating from Wendy Maruyama's furniture design program at San Diego State University. It takes time to develop a culture of creativity in a school, and the lack of creative opportunities in both schools and homes narrows the field. Students need to have experience in the feelings, and pleasure of accomplishment to discover the inner will to create. But, UALR is off to a steady start. My thanks are offered to studio technician John Bruhl for his help during the classes.

I am back home after a long weekend in Little Rock, teaching at the Applied Design Center in their furniture design program. I taught furniture design the first day, leading the students through an investigation of design, then beginning the making of a walnut coffee table, the top of which can be seen the in the photo above. The second day, I taught box making as shown below. The furniture program at UALR is in its second year, and is gathering momentum. It has a new director, Mia Hall, who grew up in southern Sweden where she studied Sloyd. She came to UALR after graduating from Wendy Maruyama's furniture design program at San Diego State University. It takes time to develop a culture of creativity in a school, and the lack of creative opportunities in both schools and homes narrows the field. Students need to have experience in the feelings, and pleasure of accomplishment to discover the inner will to create. But, UALR is off to a steady start. My thanks are offered to studio technician John Bruhl for his help during the classes.Last night I made my presentation on the Wisdom of the Hands at the Arkansas Art Center. The audience was small but wonderfully engaged and responsive, and made me feel at home and comfortable despite some technical difficulties with my presentation.

I spent the weekend with friends in their home, full of beautifully crafted objects, each invested with love and attention beyond comprehension, and each expressing exquisite beauty, making me wonder why most people settle for so much less, allowing their lives to be cluttered and overwhelmed with emotionless, hollow, meaningless manufactured objects. But anyway, it is great to be home, with my own tools and the opportunity to be back at work, making beautiful things.

Wednesday, November 14, 2007

I will probably be out of blog range for a few days. I leave tomorrow morning for my weekend of classes in Little Rock. One of the things I've done in preparation for my lecture at the Arkansas Arts Center is save the past 14 months of blog entries for review. I'll be cramming. The hands are hard to get a handle on... to get a grasp of the full significance of their engagement in human life. So to provide a simple overview of the Wisdom of the hands can be a monumental task. At best, I hope my talk will at least cause the audience to reflect on their own hands. Getting a grip on the hands is like turning a corner and finding a whole new city that has been there your whole life, but that you suddenly discover for the first time.

Check back. If you find nothing new, read some entries in the archive. If I have a chance, I'll make a post or two from Little Rock.

Check back. If you find nothing new, read some entries in the archive. If I have a chance, I'll make a post or two from Little Rock.

As shown in the photos above, the 5th and 6th grade students finished their bookends this morning. While some finished the sawing, sanding and assembly, others applied the oil finish, and filled the time waiting their turn by carving pens. Each had the opportunity to do everything, so we will have pens to finish after we return from Thanksgiving break.

As shown in the photos above, the 5th and 6th grade students finished their bookends this morning. While some finished the sawing, sanding and assembly, others applied the oil finish, and filled the time waiting their turn by carving pens. Each had the opportunity to do everything, so we will have pens to finish after we return from Thanksgiving break. I keep getting wonderful feedback from my students, about how much fun they have in woodshop, and I believe you can see in the photos that they are growing both in the quality of their crafsmanship and also in the confidence expressed in their designs. In the meantime, I'm gathering the things I need for my weekend of classes in Little Rock and to make a delivery of boxes to the gallery there that represents my work.

There are three levels of evidence in investigation of phenomena. Personal experience, anecdotal (referencing the experience of others), and statistical. Most commonly in America, statistical evidence is most highly regarded because it is most difficult to clearly understand, and requires the most complicated investigation. As a point of interest, statistical evidence is easy to manipulate in the hands of experts and those with devious or malicious intent. A classic text by Darrell Huff, How to Lie with Statistics, would help any modern citizen to get it. But remember, statisticians have gotten even better at misrepresentation since 1954 when the book was written.

Removal of direct experience from education in America places us all at risk, as we become more distanced from reliance on our own senses and sensibilities for judging the truth and merit of information presented to us as fact. Working with real physical material in a woodshop is a valuable means of developing sensitivity and trust of the senses, and provides a foundation for later scientific investigation and personal analysis.

Is education in America intended to develop an enlightened and intelligent citizenry or blind obedience to our masters? You guess.

Removal of direct experience from education in America places us all at risk, as we become more distanced from reliance on our own senses and sensibilities for judging the truth and merit of information presented to us as fact. Working with real physical material in a woodshop is a valuable means of developing sensitivity and trust of the senses, and provides a foundation for later scientific investigation and personal analysis.

Is education in America intended to develop an enlightened and intelligent citizenry or blind obedience to our masters? You guess.

Tuesday, November 13, 2007

"Career and Technical Education is ideally suited to teaching students the soft skills needed to succeed in the 21st century workplace."--Ed Bronson

The following is from a new article, Helping CTE students L(earn) to their Potential by a friend Ed Bronson, assistant director of Career and Technical Education for the Madison-Oneida BOCES in Verona, New York.

The following is from a new article, Helping CTE students L(earn) to their Potential by a friend Ed Bronson, assistant director of Career and Technical Education for the Madison-Oneida BOCES in Verona, New York.

A recent survey of 400 leading American corporations by the Partnership for 21st Century Skills notes that managers consider 70 percent of high school graduates lacking professionalism and work ethic skills. A 2005 survey by the American Society for Training and Development reached similar conclusions. Ever since the education secretary’s Commission on Achieving Necessary Skills (SCANS 1992), American corporations have been imploring schools to better prepare graduates for the world of work. Along with an obvious need for a solid foundation in SCANS skills such as core academics, the need for good interpersonal and personal skills such as responsibility, self-esteem and integrity were also emphasized. These latter qualities are widely described as “soft” skills because they tend to be tricky to scientifically measure and are believed to be even trickier to somehow attempt to teach.In the article Ed proposes a variety of useful means to actively impart positive values in the learning process. The article is published by www.acteonline.com

Processing Experience-- Teachers commonly express frustration with what they perceive to be a widespread lack of emotional intelligence among high school students and wonder to what extent important employability skills can actually be taught. In order to make real progress with students needing to develop transferable employability skills, the students must first be ready to consider the worth of having such skills. The best way to do this is by facilitating student reflections on learning.

Today the words "formal education" refer to learning that takes place within the context of established educational institutions, as contrasted with "informal" education in which students learn on their own, self-motivated and self-directed.

Back in the late 1800's and early 1900's, the words "formal education" had a distinctly different meaning, particularly when used by Otto Salomon, director of the Sloyd Teacher School at Nääs or by one of his students. The following is from Hans Thorbjörnsson, Swedish historian and curator of Otto Salomon's library at Nääs:

Back in the late 1800's and early 1900's, the words "formal education" had a distinctly different meaning, particularly when used by Otto Salomon, director of the Sloyd Teacher School at Nääs or by one of his students. The following is from Hans Thorbjörnsson, Swedish historian and curator of Otto Salomon's library at Nääs:

"In Swedish language Salomon is using the terms (expressions) ”formell bildning”, ”formell uppfostran” och ”formella ma.l”. In The Theory of Educational Sloyd they are translated ”formative education” (education meaning both bildning och uppfostran) and “formative goals”. You are quite right interpreting the Swedish formell as general competence, character development, citizenry and responsibility. Salomon talked about the child’s development morally, intellectually and physically being promoted during sloyd work. For the mere sloyd skills (handling tools and material/wood) he used the terms “materiella ma.l” (material goals) and “materiell utbildning”. In The Theory of Educational Sloyd the Swedish terms are translated utilitarian goals / utilitarian education."This simple term, in Swedish, "formell" or in English, "formative" or "formal" recognize the wood shop's goals of shaping lives as well as giving shape to wood. As any shop teacher or former shop teacher can tell, there are important things going on as children engage in the process of working with wood. Sure, they are developing skills in the use of their hands that would benefit society were they to become carpenters, craftsmen, engineers or surgeons, but they are doing much more. In our current political and cultural climate with our obsessive concern to teach those things we can measure on standardized tests, we have largely forgotten what those other things are.

Monday, November 12, 2007

Notice of classes and lecture event. This weekend I'll be teaching furniture design and box making in two one day classes at the University of Arkansas, Little Rock. The enrollment is open and there are no costs to attend. Friday, November 16, the subject will be furniture design, and I will be making a walnut dining table. On Saturday, the subject will be box making. I will be demonstrating a variety of jigs that will make box making easy and accurate, and have a display of boxes used in the illustrations of my various books. Classes are from 9 AM to 5 PM with a break for lunch and will be held in the Furniture Design Studio at 5820 Asher Avenue, Little Rock, AR 72204. Use Google if you need a map or driving instructions.

On Sunday, November 18, I'll make a presentation on my work and woodworking education for the Friends of Contemporary Crafts in the lecture hall at the Arkansas Arts Center starting at 6 PM. The Arkansas Arts Center is located at 501 E. 9th Street Little Rock, AR 72202

On Sunday, November 18, I'll make a presentation on my work and woodworking education for the Friends of Contemporary Crafts in the lecture hall at the Arkansas Arts Center starting at 6 PM. The Arkansas Arts Center is located at 501 E. 9th Street Little Rock, AR 72202

The following quote, an extremely clear discussion of the educational value of manual training in schools is from the preface of Woodwork, The English Sloyd by S. Barter, 1892:

Manual Instruction, especially when wood is the material used, may be nothing more than the development of mechanical skill in the use of tools; and, as such, it is understood by many of its advocates. But this is not what 'Educators' conceive Manual Training to be. The Manual Training of the school must be a training which places intellectual and moral results before mechanical skill. If I may venture on a definition, I should say that Manual Training is a special training of the senses of sight, touch, and muscular perception by means of various occupations and it is a training of these faculties not so much for their own sake, though that is important, as it is for the training of the mind. While the eye is being trained to accuracy and the hand to dexterity and manipulative skill, the mind is being trained to observation, attention, comparison, reflection, and judgment. In other words, Manual Training is a development of the manual and visual activities of the child, having for its purpose to quicken and develop the mental powers of observation, attention, and accuracy; to cultivate the moral faculties of order and neatness, perseverance and self-reliance; to awaken and train the artistic faculties, and direct the child's instincts towards the beautiful and true; to satisfy and cultivate the child's instinct for activity, and excite pleasure in the acquisition of skill; to provide opportunity for the development and practice of the inventive and constructive faculties; and to afford scope for the imagination.

Thus the main aim of Manual Training is Educational, to perfect our system of education, and so to raise the standard of practical intelligence throughout the community. At the same time some other advantages follow, which, if secondary, are important. For instance, the special training of hand and eye cannot fail to develop and stimulate those faculties upon whose activity success in life depends. The cultivated taste, the trained eye, and the skilled hand cannot fail to bring forth fruit in the home and in the workshop, and, in fact, in whatever position in life the child may be placed. Then, again, Manual Training confers a marked benefit on the school. It attracts and delights the children, because here they find food for the imperious need of activity inherent in child nature. Manual Training lightens and brightens the work of the school, and introduces an element of attractiveness which must relieve school-life of some of the weariness and languor incidental to purely mental effort.

One word more: the essence of Manual Training lies in the practice, and not in the production; in the doing, not in the thing done; and any exercise is valuable only in proportion to the demand it makes upon the mind for intelligent, thoughtful work.

GEORGE RICKS, B.Sc.

Sunday, November 11, 2007

One of the major challenges in American schools is that of maintaining a high level of civility. Schools are plagued by rude behavior, classroom disruption, and bullying. Teachers as a result, often leave the profession in as few as three years or less. So imagine, after spending 4 years on your college education, and with the amount of investment and debt that entails, leaving your chosen profession in discouragement. Imagine also, the students (and parents) who were disappointed in their educational aspirations by a faulty learning environment. Imagine the ultimate toll on the American economy of people left in the margins of economic utility and stunted in their creative power.

So what does that have to do with manual arts?

Here in the U.S. our Constitution guarantees freedom of religion, and in order to assert and protect that guarantee, the Constitution provides for separation of church and state. This means that in our state supported schools, organized worship and prayer, and the promotion of specific religions and specific religious beliefs are prohibited.

Many Christian conservatives in the United States promote the idea that organized prayer in our schools and the promotion of Christian values would lead in a restoration and revitalization of moral values and behavior in schools.

While I would not question the value of meditation or prayer, I suggest that Christ was a carpenter before he became so widely known and promoted as the Christian Savior. There are significant human values expressed in and learned from craftsmanship, and the greatest failure in American schools is not the prohibition of organized prayer, but the disengagement of the hands in the skillful exploration of learning and making.

I would like to share an old saying. "Idle hands are the devil's workshop." Can you see a similarity between the word workshop and "worship"? Put the hands back in education, let our schools become workshops with children making things of usefulness and beauty, and you will see other things happening as well. When children have the pride of self and confidence that arises from successful engagement in making beautiful things, civility will arise also. So the answer to improving American education is not to be found in hands folded idly in prayer, but in the carpenter's hands--- training, skill, service and devotion.

So what does that have to do with manual arts?

Here in the U.S. our Constitution guarantees freedom of religion, and in order to assert and protect that guarantee, the Constitution provides for separation of church and state. This means that in our state supported schools, organized worship and prayer, and the promotion of specific religions and specific religious beliefs are prohibited.

Many Christian conservatives in the United States promote the idea that organized prayer in our schools and the promotion of Christian values would lead in a restoration and revitalization of moral values and behavior in schools.

While I would not question the value of meditation or prayer, I suggest that Christ was a carpenter before he became so widely known and promoted as the Christian Savior. There are significant human values expressed in and learned from craftsmanship, and the greatest failure in American schools is not the prohibition of organized prayer, but the disengagement of the hands in the skillful exploration of learning and making.

I would like to share an old saying. "Idle hands are the devil's workshop." Can you see a similarity between the word workshop and "worship"? Put the hands back in education, let our schools become workshops with children making things of usefulness and beauty, and you will see other things happening as well. When children have the pride of self and confidence that arises from successful engagement in making beautiful things, civility will arise also. So the answer to improving American education is not to be found in hands folded idly in prayer, but in the carpenter's hands--- training, skill, service and devotion.

Saturday, November 10, 2007

It has been so beautiful here in Arkansas today. I spent most of the day in the yard, hauling leaves, trimming branches on trees and preparing the gardens for winter. Our colors turned a bit late this year, perhaps due to the hard freeze we had after the trees were all leafed out in the spring. I have a few leaves in their fall colors for your viewing pleasure Here! The leaves shown at left are Sycamore, and the ones below are Sugar Maple.

It has been so beautiful here in Arkansas today. I spent most of the day in the yard, hauling leaves, trimming branches on trees and preparing the gardens for winter. Our colors turned a bit late this year, perhaps due to the hard freeze we had after the trees were all leafed out in the spring. I have a few leaves in their fall colors for your viewing pleasure Here! The leaves shown at left are Sycamore, and the ones below are Sugar Maple.

I have had a busy week dealing with publishers, all good news. I am starting a new book and DVD for Taunton Press about making rustic furniture. The contract should be ready next week. Fine Woodworking has agreed to publish some of my projects for kids as a regular feature on the Fine Woodworking Website. And in addition, two box making articles I wrote for Fine Woodworking will be published in the spring and summer, so I am busy packing boxes to ship them to Connecticut for studio photography.

Now, in honor of boxes, wooden boxes, the objects that got me into writing and publishing in the first place I will share a few words of Dr. Felix Adler from an address delivered before the National Conference of Charities and Correction, Buffalo, New York 1888:

Now, in honor of boxes, wooden boxes, the objects that got me into writing and publishing in the first place I will share a few words of Dr. Felix Adler from an address delivered before the National Conference of Charities and Correction, Buffalo, New York 1888:

By manual training we cultivate the intellect in close connection with action. Manual training consists of a series of actions which are controlled by the mind, and which react on it. Let the task assigned be, for instance, the making of a wooden box. The first point to be gained is to attract the attention of the pupil to the task. A wooden box is interesting to a child, hence this first point will be gained. Lethargy is overcome, attention is aroused. Next, it is important to keep-the attention fixed on the task: thus only can tenacity of purpose be cultivated. Manual training enables us to keep the attention of the child fixed upon the object of study, because the latter is concrete. Furthermore, the variety of occupations which enter into the making of the box constantly refreshes this interest after it has once been started. The wood must be sawed to line. The boards must be carefully planed and smoothed. The joints must be worked out and fitted. The lid must be attached with hinges. The box must be painted or varnished. Here is a sequence of means leading to an end, a series of operations all pointing to a final object to be gained, to be created. Again, each of these becomes in turn and for the time being a secondary end; and the pupil thus learns, in an elementary way, the lesson of subordinating minor ends to a major end. And, when finally the task is done, when the box stands before the boy's eyes a complete whole, a serviceable thing, sightly to the eyes, well-adapted to its uses, with what a glow of triumph does he contemplate his work! The pleasure of achievement now comes in to crown his labor; and this sense of achievement, in connection with the work done, leaves in his mind a pleasant after-taste, which will stimulate him to similar work in the future. The child that has once acquired, in connection with the making of a box, the habits just described, has begun to master the secret of a strong will, and will be able to apply the same habits in other directions and on other occasions.

Or let the task be an artistic one. And let me here say that manual training is incomplete unless it covers art training. Many otherwise excellent and interesting experiments in manual training fail to give satisfaction because they do not include this element. The useful must flower into the beautiful to be in the highest sense useful.

I was reading this morning in another woodworking blog The Craftsman's Path about the legacy left by an old woodworker. This story by Mark Mazzo reminded me of an old friend and I felt inclined to add my own comments, which are as follows:

I had a friend, Tommy Thomas, who was a retired art teacher from the Kansas City Art Institute. He was a great painter, a good woodworker, and it was the woodworking he truly loved. He came by one day with a gift of a complete set of Bracht mortising chisels. These were tools that had been given to him, and that he decided to hold out from the auction of the rest of his shop which consisted of both old and new tools which he had bought for himself. He was dying of cancer. I went to his auction and bought a few more things. Each reminds me of him, and as these things were old before he bought them, they remind me of an unbroken chain. That legacy you speak of is not something one man leaves, but something that passes through the lives of those of us who love working with wood. It connects us each with the best part of what it is to be human. Each small decision we make connects us with and reflects higher purpose. At some point, my own shop will be distributed. If I am lucky, I’ll know some woodworker in the neighborhood who will receive a complete set of Bracht chisels.

But frankly, we are a nation of idiots. We spend millions of dollars on laptops so our children can be distracted and entertained instead of creative and engaged. If they are quiet in their rooms, we think they are OK. But they need to be pounding and hammering things in our shops, sawing, cooking sewing, and learning the highest values of human life.

Friday, November 09, 2007

If you walk on a pathway in the woods, you notice the worn area where other feet have traveled before your own. There may even be the foot prints left in soft clay. If you follow that path for the first time, at each side is undifferentiated green. Being able to recognize the difference between the path and the green can be enough knowledge to carry you to your destination. And yet, who would not be awakened to greater curiosity? There are scents, sights, sounds and textures that stimulate your attention. There is a sequential quality to the experience, providing an organizational framework for ease of remembrance. You start at one end and journey to the other. It is best to travel with a trusted friend and mentor who can share the names of things, and point out relationships between things that you can examine and explore for yourself. In time, the variations in the path and the forest are revealed to you both in name and comprehension... an infinite revelation of simplicity and complexity.

Here we have the beginnings of school. The ideal school and learning environment.

Next we are joined by others and we walk in town. We see people at work and in activities that seem strange to us. But again, the trusted friend and mentor helps in the naming of things and description of relationships that we can observe and study for our own understanding. There are scents, sights, sounds and textures to awaken curiosity, and a sequential quality that unfolds, revealing life in a manner in which it can be remembered and explored.

Do you get the idea here? Any questions so far? It is another beautiful day in the Ozark Mountains of Arkansas. The kids at school have been playing dodge ball at recess. The teachers stand by as referees. Cheering for each. You would have to come see for yourself to fully comprehend the essential qualities involved.

Here we have the beginnings of school. The ideal school and learning environment.

Next we are joined by others and we walk in town. We see people at work and in activities that seem strange to us. But again, the trusted friend and mentor helps in the naming of things and description of relationships that we can observe and study for our own understanding. There are scents, sights, sounds and textures to awaken curiosity, and a sequential quality that unfolds, revealing life in a manner in which it can be remembered and explored.

Do you get the idea here? Any questions so far? It is another beautiful day in the Ozark Mountains of Arkansas. The kids at school have been playing dodge ball at recess. The teachers stand by as referees. Cheering for each. You would have to come see for yourself to fully comprehend the essential qualities involved.

Thursday, November 08, 2007

The weather here in Arkansas has been perfect all week. All the Clear Spring High School students have been studying Ornithology, so while nearly every other teacher in Arkansas has been contending with the question, "Can't we please go outside?" ...and having to say no, the Ornithology class has been outside nearly every day... except today. This afternoon they came to the wood shop and we made 11 bird feeders of 3 different types... a large window feeder for their classroom window, six small seed feeders to hang on trees around the campus and 4 suet feeders to attract woodpeckers. I was much too busy directing and cutting stock to take any photos, but we had a great time. And if you can't be in the woods on such a beautiful day, being in the wood shop is the next best thing.