The Philadelphia Centennial exposition, 1876, ten years after the close of the American Civil War, and during the second term of President Ulysses S. Grant was intended to celebrate the centennial of the Declaration of Independence in the city of our nation’s birth. It also charted the course for rapid American industrial expansion. In the great hall of industry, visited by many thousands, a single huge Corliss Steam engine ran 13 acres of through more than a mile of shafts.

The Philadelphia Centennial exposition, 1876, ten years after the close of the American Civil War, and during the second term of President Ulysses S. Grant was intended to celebrate the centennial of the Declaration of Independence in the city of our nation’s birth. It also charted the course for rapid American industrial expansion. In the great hall of industry, visited by many thousands, a single huge Corliss Steam engine ran 13 acres of through more than a mile of shafts. The engine had a 44 inch bore, 10 foot stroke, was more than 45 feet tall, had a fifty-six ton, thirty foot diameter, twenty-four inch face flywheel, and produced 1,400 Horse Power at 36 RPM.

But the introduction of modern industry was not the only lasting effect of the exhibition. Two particular educational methods went from obscurity to mainstream. Victor Dela Vos display of the “Russian System” of manual training showed how schools might prepare students for futures in the industrial age. Calvin Woodward of Washington University and John D. Runkle of MIT were impressed, went home to their universities, established programs of manual training and thus became the co-fathers of the manual arts movement in the US. A growing industrial nation would not only need the machinery produced by Corliss and others as demonstrated in the halls of industry, it would need trained and nimble hands and minds to feed the machinery of American progress.

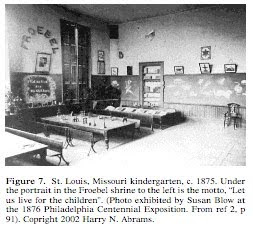

The other exhibit that had lasting effect was far simpler and much more gentle than the rumble of belts and line shafts and the thrust of steam propulsion, but its impact was equally profound. It consisted of a “Kindergarten Cottage” with an actual kindergarten classroom set up by the Froebel Society of Boston in which a trained teacher, Ruth Burritt, taught orphans 3 days per week. Burritt explained the method to thousands of visitors as the children followed “a typical kindergarten routine of playing, singing, movement games and manipulating Froebel’s gifts.” As described by Nina C. Vandewalker: “The enclosure for visitors was always crowded, many of the onlookers being hewers of wood and drawers of water who were attracted by the sweet singing and spellbound by the lovely spectacle.”

And so we see an exposition, contrasting gentleness of learning with the explosion of American industrial power. But there was a vision that brought the two into a heartful combination. Educational sloyd. When Uno Cygnaeus developed the folk schools of Finland, based on his desire to extend Frobel’s kindergarten theories into the upper grades, craft (sloyd or käsityön) was the method through which children would continue their learning, hands on. As described by Salomon and his followers, the Russian system of Della Vos and as introduced to the American public at the Philadelphia Exposition of 1876 had economic purposes, propelling students into industrial performance, crafts and educational sloyd in schools had “formative” or developmental effects. The idea was to lead the children onward in growth of skill, character and intellect by engaging their natural love of making things. It is the difference between pushing and pulling a rope.

The photos above and below: Corliss steam engine at Philadelphia Exposition, and Susan E. Blow's St. Louis classroom as displayed at the 1876 Exposition.

Such a simple idea, to let kids learn by doing things they enjoy.

ReplyDeleteMario

This is a beautiful post about an important era.

ReplyDelete