This blog is dedicated to sharing the concept that our hands are essential to learning- that we engage the world and its wonders, sensing and creating primarily through the agency of our hands. We abandon our children to education in boredom and intellectual escapism by failing to engage their hands in learning and making.

Monday, June 30, 2008

There are a lot of things these days that could scare the bejesus out of you. Escalating gas prices are one. Of course frightening things have a way of sneaking up on you even though they've been looming on the horizon for a long time. One of the things that is still out there actually came up in 1993 when Howard Gardner published Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences which obviously does two things. First it tells us that people are smart in a variety of ways, and secondly it tells us that we learn in different ways as well. There is a third thing it tells us that is pushed aside and must be reckoned with if we are to raise general intelligence to a high enough level to deal with all the other issues that result from an overstressed planet. That third thing is to take note that despite our mind numbing technologies we really aren't as smart as we think we are or as smart as we would have been if the full range of human intelligences were acknowledged and rewarded.

We have school systems in which only one form of intelligence is truly valued... That which can be effectively and easily tested. We have public schools and universities dominated by that form of intelligence to the direct and purposeful exclusion of other forms. (except the token athletics kept to inspire school spirit.) We cope each day with a system dominated by an intelligentsia which had been deprived of the mind developing, problem solving, character building hands-on learning which would have made them wise, while we have an underclass deprived of the confidence for life-long learning that recognition of their multiple intelligences would have offered toward their success.

Educational Sloyd was proposed for the learning of all. For one thing, the use of the hands helped in the development of intelligence for all students. Even those who lacked the basic capacity for skilled and efficient use of the hands, were able at least to come to an appreciation and acknowledgment of the hands-on intelligence of others.

Is this too much of a leap to make? Can you see the connection? Unfortunately through the workings of the ego, academia is heavily invested in a sense of superiority. It is the way things work. It is a case of the emperor's clothes, and until someone has had the opportunity and challenge of learning through their own hands, they just won't get it. They will parade defiantly naked and oblivious to the truth. No doubt my discussion would raise the ire of those academicians whose positions are maintained through a false sense of superiority. For those of us who see in each day's activities, the intelligence expressed in making things, this idea is a no-brainer. Join me in promoting it.

We have school systems in which only one form of intelligence is truly valued... That which can be effectively and easily tested. We have public schools and universities dominated by that form of intelligence to the direct and purposeful exclusion of other forms. (except the token athletics kept to inspire school spirit.) We cope each day with a system dominated by an intelligentsia which had been deprived of the mind developing, problem solving, character building hands-on learning which would have made them wise, while we have an underclass deprived of the confidence for life-long learning that recognition of their multiple intelligences would have offered toward their success.

Educational Sloyd was proposed for the learning of all. For one thing, the use of the hands helped in the development of intelligence for all students. Even those who lacked the basic capacity for skilled and efficient use of the hands, were able at least to come to an appreciation and acknowledgment of the hands-on intelligence of others.

Is this too much of a leap to make? Can you see the connection? Unfortunately through the workings of the ego, academia is heavily invested in a sense of superiority. It is the way things work. It is a case of the emperor's clothes, and until someone has had the opportunity and challenge of learning through their own hands, they just won't get it. They will parade defiantly naked and oblivious to the truth. No doubt my discussion would raise the ire of those academicians whose positions are maintained through a false sense of superiority. For those of us who see in each day's activities, the intelligence expressed in making things, this idea is a no-brainer. Join me in promoting it.

Sunday, June 29, 2008

I saw one of my former students today, shown here at the lathe in 2003. She is now an art student in college, majoring in graphic design. She had great fun last week, she told me. One of her friends bought a lathe and didn't know how to use it. So my former student became teacher. It is a wonderful thing when that happens.

She is now an art student in college, majoring in graphic design. She had great fun last week, she told me. One of her friends bought a lathe and didn't know how to use it. So my former student became teacher. It is a wonderful thing when that happens.

She is now an art student in college, majoring in graphic design. She had great fun last week, she told me. One of her friends bought a lathe and didn't know how to use it. So my former student became teacher. It is a wonderful thing when that happens.

She is now an art student in college, majoring in graphic design. She had great fun last week, she told me. One of her friends bought a lathe and didn't know how to use it. So my former student became teacher. It is a wonderful thing when that happens.

I have three interesting email conversations today, all seemingly in the same theme. Jo Reincke in Germany suggests reading Karl Raimond Popper, a famous philosopher who started out as a cabinet maker. This is in support of my contention that a hands-on approach is preferable to a purely academic one.

The following is from an old college friend George Lundeen, a sculptor whose work was shown here a couple days ago and which you will find below:

In the same vein, Joe Barry sent the following:

The following is from an old college friend George Lundeen, a sculptor whose work was shown here a couple days ago and which you will find below:

The schools have dropped the ball when it comes to teaching. I think your ideas about working with your hands and creating something has a much deeper and life lasting effect on anyone who ever has that chance. This past year, my son was taking an Art History class and was totally bored and frustrated that he had to sit and watch slides and listen to a teacher who simply read from the text or remembered what her teacher had read from the text. In a meeting I had with her I told her of a couple teachers who I thought were the best Art teachers and how they had brought the art to the students by having the students make art and incorporate the creativity into the history. Sadly she said she had her way of teaching and had not had a problem with the administration about her performance. A hands on approach would, I think work wonders with many disciplines in the educational field. After all isn't that what we all do, when we leave academia, join the unwashed and have to learn how to finally do something in order to survive? How fortunate are we to have found something to keep our minds and hands busy for so long and been able to feed our families and thrive.George, very well put. And yes, you and I are very lucky. A friend of mine here in Arkansas just retired as an art history teacher and he had confided in me that in all his thirty-five years of teaching he never had a potter get higher than a B. We do pottery (or woodworking) because we don't want to sit in dark rooms and hear lectures. He was a good teacher and is a great friend, but it was way too much work for the amount of time available for him to bring clay into the classroom. Besides, the purpose of art history isn't to make people qualified as artists, but to give a sense of mastery through the left brain activities of classifying and categorizing the arts to those who haven't a chance in hell of doing any of it. That way people who really don't have a clue about visual and tactile creativity can feel superior to those whose lives are driven by it.

I think it's time to build a pottery shop in the barn and get back to teaching a few kids including my own how much fun it is and how simple it is to make something useful from the earth....the most useful thing being the doing itself!

In the same vein, Joe Barry sent the following:

In my day job as therapist I often run into academics and their skewed world view. The feedback that they have been getting for years from students and preceptors after internships is the need for more practical (ie: hands on) training. The curriculum is full of courses on research and has minimal practical work because "you'll learn that when you do your internship". They now want to follow the Physical Therapists down the rabbit hole and require a doctorate as an entry level requirement. That's just what we need - another year of coursework on doing research and no contact with real patients and the real business of treating people. (Plus, salaries are not rising with the increased debt load of a 5-6 year college education. New grads will not make enough money to pay their loans off)

A book for you: The Reflective Practitioner by Donald Schon. He examines how people improve in practice by reflecting on their experience and changing what they are doing in order to do it better. (Hmmm, belt sander and 40 grit belt not a good idea!)

Francis Bacon: It is “esteemed a kinde of dishonour to descend to enquirie or Meditation upon Matters Mechanicall.” The Two Bookes Of the proficience and advancement of Learning, divine and humane. London (1605)

So maybe it's a tradition.

According to this article in the London Telegraph, Ofsted: Children missing out on woodwork Even science experiments are being eliminated from children's education as teaching to the test takes precedence over hands-on experience in schools.

It provides very little satisfaction to note that we in the US are not alone in our idiocy.

It is interesting that in many publications, having information properly footnoted is of greater importance than direct experience in the subject matter, but that has not always been so. The following is from the 2002 WAG Postprints:The History and Technology of Waveform Moldings: Reproducing and Using Moxon’s “Waving Engine” by Jonathan Thornton

As we strip our schools of hands-on activities and learning, we also strip our next generation of researchers from understanding the necessary and fundamental relationship between research and first-hand observation of subject matter. Just how dumb can we get? We'll see.

So maybe it's a tradition.

According to this article in the London Telegraph, Ofsted: Children missing out on woodwork Even science experiments are being eliminated from children's education as teaching to the test takes precedence over hands-on experience in schools.

It provides very little satisfaction to note that we in the US are not alone in our idiocy.

It is interesting that in many publications, having information properly footnoted is of greater importance than direct experience in the subject matter, but that has not always been so. The following is from the 2002 WAG Postprints:The History and Technology of Waveform Moldings: Reproducing and Using Moxon’s “Waving Engine” by Jonathan Thornton

Joseph Moxon was the son of the radical Puritan printer James Moxon, who was exiled to Holland with his family from 1637–43. Joseph learned the printing trade from his father, and pursued it on his own after he returned to England. In addition to printing, he made and sold globes and instruments for mathematics and navigation. He designed and cut type, and wrote the first book on the art of printing. With these various activities, Moxon became of necessity something of a jack-of-all- trades. He writes as one who has seen or done all of the things he describes. It is for this reason that his works were so influential...Thornton's article about an interesting way to carve wave-like forms in wood is a good example of blending academic research with hands-on efforts at duplication of technique. Like the archaeologist who learns to nap flint in his efforts to better understand the artifacts and peoples he studies, the path of the maker is a bit different from that of the purely academic researcher. We take things and test them in our own hands. If we have an idea, instead of searching old literature, we try things in the woodshop or outside the conventional classroom. There may be some redundancy in our efforts. There may be some mistakes made. But what we report as our findings will have the ring of truth that emerges from the sincerity of our efforts.

As we strip our schools of hands-on activities and learning, we also strip our next generation of researchers from understanding the necessary and fundamental relationship between research and first-hand observation of subject matter. Just how dumb can we get? We'll see.

Saturday, June 28, 2008

The Diablo Woodworkers in the San Francisco Bay area has held their first annual high school competition. From the slide show, you can see that it was a success!  The Diablo woodworkers had been concerned that high school woodworking would become a thing of the past. The summer before last they completely restored a high school woodshop to prepare for my box making class. This year, the start of a high school competition was an amazing amount of work, but something they plan to do again in addition to all their other public service and community involvement efforts.

The Diablo woodworkers had been concerned that high school woodworking would become a thing of the past. The summer before last they completely restored a high school woodshop to prepare for my box making class. This year, the start of a high school competition was an amazing amount of work, but something they plan to do again in addition to all their other public service and community involvement efforts.

High School competitions are great ways to do two things. Stimulate quality work, and stimulate community interest. Congratulations to the Diablo Woodworkers, and to all the students and teachers involved. Each piece you see is not just an object made, but an embodiment of learning, effort and creativity. The Diablo Woodworkers just did a very cool thing. They informed students that others in the community are interested and supportive of their success, they told school administrators how important woodworking programs are to their communities and they informed all that the hands are still important in education. The competition was featured in the Contra Costa Times.

High School competitions are great ways to do two things. Stimulate quality work, and stimulate community interest. Congratulations to the Diablo Woodworkers, and to all the students and teachers involved. Each piece you see is not just an object made, but an embodiment of learning, effort and creativity. The Diablo Woodworkers just did a very cool thing. They informed students that others in the community are interested and supportive of their success, they told school administrators how important woodworking programs are to their communities and they informed all that the hands are still important in education. The competition was featured in the Contra Costa Times.

The Diablo woodworkers had been concerned that high school woodworking would become a thing of the past. The summer before last they completely restored a high school woodshop to prepare for my box making class. This year, the start of a high school competition was an amazing amount of work, but something they plan to do again in addition to all their other public service and community involvement efforts.

The Diablo woodworkers had been concerned that high school woodworking would become a thing of the past. The summer before last they completely restored a high school woodshop to prepare for my box making class. This year, the start of a high school competition was an amazing amount of work, but something they plan to do again in addition to all their other public service and community involvement efforts.  High School competitions are great ways to do two things. Stimulate quality work, and stimulate community interest. Congratulations to the Diablo Woodworkers, and to all the students and teachers involved. Each piece you see is not just an object made, but an embodiment of learning, effort and creativity. The Diablo Woodworkers just did a very cool thing. They informed students that others in the community are interested and supportive of their success, they told school administrators how important woodworking programs are to their communities and they informed all that the hands are still important in education. The competition was featured in the Contra Costa Times.

High School competitions are great ways to do two things. Stimulate quality work, and stimulate community interest. Congratulations to the Diablo Woodworkers, and to all the students and teachers involved. Each piece you see is not just an object made, but an embodiment of learning, effort and creativity. The Diablo Woodworkers just did a very cool thing. They informed students that others in the community are interested and supportive of their success, they told school administrators how important woodworking programs are to their communities and they informed all that the hands are still important in education. The competition was featured in the Contra Costa Times.

Friday, June 27, 2008

This morning as I was sanding the curved back for the rustic chair, I couldn't help thinking in nautical terms. The word in mind was fair. When the hand passes of over the shape of something, it is far better than the eye at noting qualities of form, and fair is the nautical term meaning smooth and even, without inappropriate variation.

I have fallen in love with the magazine Wooden Boat and I picked up the August issue at the book store this afternoon and plan to subscribe. There is no greater force in the restoration of the hand to its rightful place in human culture than the love of crafting wooden boats. This particular issue has a lot to offer anyone who loves wood, and there is a section devoted to understanding the lumber required for making boats.The magazine is full of practical advice on making and caring for wooden boats, but it also contains such things as the following by author Lawrence W. Cheek in an essay called "Perfectionism and the Wooden Boat:

I have fallen in love with the magazine Wooden Boat and I picked up the August issue at the book store this afternoon and plan to subscribe. There is no greater force in the restoration of the hand to its rightful place in human culture than the love of crafting wooden boats. This particular issue has a lot to offer anyone who loves wood, and there is a section devoted to understanding the lumber required for making boats.The magazine is full of practical advice on making and caring for wooden boats, but it also contains such things as the following by author Lawrence W. Cheek in an essay called "Perfectionism and the Wooden Boat:

If a boat is ugly--clunkily proportioned, sloppily detailed, pocked with epoxy leprosy--it's a form of visual pollution, dishonoring human intelligence and squandering the materials that went into it. If it's beautiful, it leaves ripples of pleasure in its wake, enhancing life on Earth in some small way. The presence of beauty makes a difference in the quality of life for all humanity.

The hand/brain partnership or system is dynamic. The weight of attention required by either the hand or brain changes in relation to the amount of skill previously acquired.  If you visualize the hand or brain as weights applied through attention toward task completion, as shown in the diagram you see that in the beginning stages of skill building, most of the weight of attention is applied by the brain as it evaluates sensory feedback from the hand and eye in relationship to desired objectives.

If you visualize the hand or brain as weights applied through attention toward task completion, as shown in the diagram you see that in the beginning stages of skill building, most of the weight of attention is applied by the brain as it evaluates sensory feedback from the hand and eye in relationship to desired objectives.

In the journeyman stage, the hand and brain share an equal load.

In the stage of skill or mastery, the weight of attention required from the brain is further lessened as the hands take on more of the sensory and manipulative processing required. The interesting thing that happens at this point is that the brain's processing power is freed so that the mind can explore, plan, speculate, observe, process, imagine and then guide further creativity and the next round of skill development.

This concept which I have tried to portray in this simple diagram is the basis of Jean Jacques Rousseau' statement, "Put a young man in a woodshop, his hands work to the benefit of his brain, he becomes a philosopher, while thinking himself only a craftsman."

I realize this is an overly simplistic illustration. The hands are not merely these things that are wiggling around at the ends of our wrists. The musculature that drives them extends way up the arms, and by wiggling your fingers, you can observe that musculature at work. Neurologically, the hands are inseparable from normal brain function. So it may be absurd to regard them as separate. It is equally absurd to think we can educate the minds of Americans without paying special attention to the education of our hands.

If you visualize the hand or brain as weights applied through attention toward task completion, as shown in the diagram you see that in the beginning stages of skill building, most of the weight of attention is applied by the brain as it evaluates sensory feedback from the hand and eye in relationship to desired objectives.

If you visualize the hand or brain as weights applied through attention toward task completion, as shown in the diagram you see that in the beginning stages of skill building, most of the weight of attention is applied by the brain as it evaluates sensory feedback from the hand and eye in relationship to desired objectives. In the journeyman stage, the hand and brain share an equal load.

In the stage of skill or mastery, the weight of attention required from the brain is further lessened as the hands take on more of the sensory and manipulative processing required. The interesting thing that happens at this point is that the brain's processing power is freed so that the mind can explore, plan, speculate, observe, process, imagine and then guide further creativity and the next round of skill development.

This concept which I have tried to portray in this simple diagram is the basis of Jean Jacques Rousseau' statement, "Put a young man in a woodshop, his hands work to the benefit of his brain, he becomes a philosopher, while thinking himself only a craftsman."

I realize this is an overly simplistic illustration. The hands are not merely these things that are wiggling around at the ends of our wrists. The musculature that drives them extends way up the arms, and by wiggling your fingers, you can observe that musculature at work. Neurologically, the hands are inseparable from normal brain function. So it may be absurd to regard them as separate. It is equally absurd to think we can educate the minds of Americans without paying special attention to the education of our hands.

Thursday, June 26, 2008

Today, I got my grant proposal off after days of work on it and now I'm back to making a rustic chair. Shown in the photos below are three steps in attaching the walnut seat. Mark the space to be cut out to conform to the shape of the legs. This has to be done at each front corner and then at the back where the seat intersects the back legs. I use a saber saw and rasp to cut out the area to fit the leg. Next while holding the seat in place drill and countersink a hole for a wood screw. Then drive the screw in place. The hole for the screw has to be drilled first to avoid splitting the wood. The band clamp around the legs holds them tight to the seat. In the third photo, I'm trimming the leg flush with the surface of the seat. Tomorrow I'll remove the seat for final sanding and then shape and fit the back. After putting it all back together, I'll apply a Danish oil finish.

On the educational value of craftsmanship... Early in my woodworking career, I realized that our American hardwoods were an under-appreciated resource. Some woods like walnut, cherry and oak were valued in the marketplace, but so many others were not. And yet, a healthy hardwood forest is diverse and every species deserves an understanding of its value. My idea was that by using some of the under-appreciated and less known hardwoods, my small boxes could serve as an environmental education tool that would help my customers to become more interested, more knowledgeable and more appreciative of our forest resources. In essence, I discovered that I could best fulfill my role as a craftsman if I were an educator as well.

Later, as I developed my business, I learned marketing. Marketing and sales are two different beasts. While you hope that marketing efforts lead to sales, marketing is really about the exchange of information with a customer base. You learn what they need, adjust what you make to meet their needs and then educate them as to the ways in which your products can meet their needs. It is more complex than selling something to someone, because it creates the kind of long term relationship that builds success year after year. Again, what we are talking about is education.

While not all craftsmen feel comfortable teaching classes, we all have a role to fill in education.

Now, for just a moment, let's look at formal education. It has systematically excluded particular learning styles throughout the history of university education. The value of hand work has been systematically denigrated since before Socrates, and then Socrates made it official... Artistry and craftsmanship were to be performed by slaves. Citizens were lowered in status by participation in such things.

My point here is not to turn tables and find fault with all those who have worked hard for their university degrees or diminish the value of their accomplishments, but to note that those who work with skill and creativity expressed through their hands are equally deserving of society's recognition and respect.

I have expressed before in the blog, the need for an affirmative action program to fully recognize the value and contributions of hands-on learners. We need to start at the other end as well. This means that we, the hands-on makers need to step forward into the full light, revealing ourselves as educators with duties and potentials beyond those of making and marketing our products. We of all American resources are the one best capable of reshaping American education.

Later, as I developed my business, I learned marketing. Marketing and sales are two different beasts. While you hope that marketing efforts lead to sales, marketing is really about the exchange of information with a customer base. You learn what they need, adjust what you make to meet their needs and then educate them as to the ways in which your products can meet their needs. It is more complex than selling something to someone, because it creates the kind of long term relationship that builds success year after year. Again, what we are talking about is education.

While not all craftsmen feel comfortable teaching classes, we all have a role to fill in education.

Now, for just a moment, let's look at formal education. It has systematically excluded particular learning styles throughout the history of university education. The value of hand work has been systematically denigrated since before Socrates, and then Socrates made it official... Artistry and craftsmanship were to be performed by slaves. Citizens were lowered in status by participation in such things.

My point here is not to turn tables and find fault with all those who have worked hard for their university degrees or diminish the value of their accomplishments, but to note that those who work with skill and creativity expressed through their hands are equally deserving of society's recognition and respect.

I have expressed before in the blog, the need for an affirmative action program to fully recognize the value and contributions of hands-on learners. We need to start at the other end as well. This means that we, the hands-on makers need to step forward into the full light, revealing ourselves as educators with duties and potentials beyond those of making and marketing our products. We of all American resources are the one best capable of reshaping American education.

Wednesday, June 25, 2008

A old friend of mine, George Lundeen is a sculptor noted for his life-size work in bronze. He sent me a photo of himself with a piece of his current work. George used to be much taller. Gravity has its effect on those of us who have been around awhile and George lives in the mountains of Colorado where the effects are horrendous. Note the custom made chair in the lower left hand corner, specially made for those of us in our shrinking years. And then think how it must feel to create something so much larger than yourself.

George used to be much taller. Gravity has its effect on those of us who have been around awhile and George lives in the mountains of Colorado where the effects are horrendous. Note the custom made chair in the lower left hand corner, specially made for those of us in our shrinking years. And then think how it must feel to create something so much larger than yourself.

George used to be much taller. Gravity has its effect on those of us who have been around awhile and George lives in the mountains of Colorado where the effects are horrendous. Note the custom made chair in the lower left hand corner, specially made for those of us in our shrinking years. And then think how it must feel to create something so much larger than yourself.

George used to be much taller. Gravity has its effect on those of us who have been around awhile and George lives in the mountains of Colorado where the effects are horrendous. Note the custom made chair in the lower left hand corner, specially made for those of us in our shrinking years. And then think how it must feel to create something so much larger than yourself.

After spending days on the computer, writing a chapter for the book, and working on a grant application to cover expenses of further research on Sloyd, I finally have gotten back to work, making a rustic chair. The photo at left shows a couple things you might want to note. You start out with the back legs and try to select your material so that the legs are roughly uniform in size and have a similar curvature. Of course these aren't hard and fast rules for chair making, but will make my work a bit easier. I have been enjoying the fact that rustic work gets me out of the shop. I get to work outside. Also, as I drive up and down our drive, I notice species of wood, noting the size and curvature, thinking "maybe I'll come back later and make something!"

After spending days on the computer, writing a chapter for the book, and working on a grant application to cover expenses of further research on Sloyd, I finally have gotten back to work, making a rustic chair. The photo at left shows a couple things you might want to note. You start out with the back legs and try to select your material so that the legs are roughly uniform in size and have a similar curvature. Of course these aren't hard and fast rules for chair making, but will make my work a bit easier. I have been enjoying the fact that rustic work gets me out of the shop. I get to work outside. Also, as I drive up and down our drive, I notice species of wood, noting the size and curvature, thinking "maybe I'll come back later and make something!"

Tuesday, June 24, 2008

Richard Bazeley is having winter break between semesters in his classes down under (Australia). Here in Arkansas we are moving into the hot days of summer.

The photo shows one of Richard's 8th year students and his interesting stool/box. I wish I'd made that myself when I was his age. Richard comments about class size:

The photo shows one of Richard's 8th year students and his interesting stool/box. I wish I'd made that myself when I was his age. Richard comments about class size:

The class sizes were around 16 this semester and proved a lot easier to manage compared with the 24 size classes I have been used to in recent years. Anyone who says that class size is not a factor in student outcomes has not taught junior woodwork.

Monday, June 23, 2008

Evidently I'm making headway. While I was unable to attend the Furniture Society Conference this year, Sloyd was there, even in my absence. John Lavine, editor of Woodwork magazine attended a woodcarving presentation. When the presenter mentioned "Sloyd carving" one of the members of the audience asked, "What is this Sloyd I keep hearing about?" Miguel Gómez-Ibáñez, director of The North Bennet St. School in Boston explained what Sloyd was and mentioned the role of his school in the start of Educational Sloyd. John Lavine piped up next. He informed the audience that while North Bennet Street School played an important role in Sloyd coming to America, Educational Sloyd really began in Finland and Sweden. He informed the audience if they want to know more about Educational Sloyd, they need to read the upcoming issue of his magazine, where an article tells about my visit to Nääs. It is a great thing that Sloyd and hands-on education are being talked about in national conferences, even when I'm not around to push the subject.

Saturday, June 21, 2008

Cedar Glen, The collections of Robyn and John Horn, by Doug Stowe

Human beings are collectors---either by accident if we stay in one place too long or on purpose if we discover a particular passion for something. You may have collected something as a child, whether pennies in a collection book or Pokeman trading cards, and you probably noticed that the quality and extent of your collection had to do with two things, your resources and your passion for the process. I collected coins as a kid, carefully going through my father’s pocket money looking for the 1909 SVDB that would have changed my fortune forever. I also filled some of the innumerable blank spaces in my collection books. For some collectors, however, there are no collection books to guide acquisitions. The scope and depth of their collecting is driven by much deeper things, as is the case with Robyn and John Horn.

Robyn and John Horn, live on an acreage called Cedar Glen west of Little Rock. After passing through their gate, you drive through a broad meadow and then enter the glen of cedars that gave the property its name. At times the cedars close in tall and tight on the road, then at points, they move back to provide an expansive view. There are large objects at a distance and others framed close at hand by the forest. Both cause you to pause, arousing your deepest curiosity. “Was that Stonehenge I just passed?” Next you cross a bridge and come to a fork in the road, marked by two stone pillars, joined at the top by a freeform arch. If you turn one way, the road leads through more fields, past a vegetable garden and various large sculptures, up the face of an earthen dam and to the Horn’s home built on the shore of a lake. If you had turned the other way, the road would have taken you winding up through the woods to a large metal building. Meanwhile, back at the fork, the arch at the top of the stone pillars is symbolic. It joins things that might seem divergent, into something unified and whole. If you like, read the arch as symbolic of the lives of John and Robyn, their combined forces brought into a cooperative whole, larger and more meaningful, but it is also symbolic of the joining of two forces in human life, to have, and the other more primal, to make.

Robyn and John Horn, live on an acreage called Cedar Glen west of Little Rock. After passing through their gate, you drive through a broad meadow and then enter the glen of cedars that gave the property its name. At times the cedars close in tall and tight on the road, then at points, they move back to provide an expansive view. There are large objects at a distance and others framed close at hand by the forest. Both cause you to pause, arousing your deepest curiosity. “Was that Stonehenge I just passed?” Next you cross a bridge and come to a fork in the road, marked by two stone pillars, joined at the top by a freeform arch. If you turn one way, the road leads through more fields, past a vegetable garden and various large sculptures, up the face of an earthen dam and to the Horn’s home built on the shore of a lake. If you had turned the other way, the road would have taken you winding up through the woods to a large metal building. Meanwhile, back at the fork, the arch at the top of the stone pillars is symbolic. It joins things that might seem divergent, into something unified and whole. If you like, read the arch as symbolic of the lives of John and Robyn, their combined forces brought into a cooperative whole, larger and more meaningful, but it is also symbolic of the joining of two forces in human life, to have, and the other more primal, to make.

John and Robyn Horn have become well known as major collectors. Their collection of American crafts has been featured in American Craft Magazine (Collecting A Life: John and Robyn Horn, Dec. 2000/Jan. 2001). It has also been the subject of an exhibit at the Arkansas Art Center, Living with Form, 2000. Objects from that exhibit are featured in a book, Living with Form, Bradley Publishing 2000. But the objects in the book are the tip of the iceberg in lives dedicated to collecting, and collecting itself can only be understood in light of the ways in which collecting, for the Horns, at least, has been an expression and enhancement of personal creativity and engagement in the arts.

When Robyn and John first met, John was a printer, and Robyn a photographer for Arkansas Parks and Tourism. They collaborated for a time as artists doing stained glass work and selling in craft fairs. The life on the craft show circuit gave John and Robyn a deep sense of appreciation for the challenges faced by artists in marketing their work. In 1984, John’s brother Sam introduced Robyn to woodturning after he returned from a week-long class with David Ellsworth at Arrowmont School of Crafts in Gatlinburg, TN. Robyn took immediately to woodturning and her own creative expression became the driving force in building a collection of works created by others. The richness of texture and form became the foundation for her own search for expression.

In 1990 the Horns bought the property at Cedar Glen and built the metal building that serves as Robyn’s studio and John’s print shop. John, continuing his passion for the printer’s art, has accumulated an incredible collection of antique printing equipment and type from back in the days before ink jets and lasers. It is not an idle collection. He works frequently in the print shop preserving the earlier technology and sharing its subtle creativity with like-minded, obsessed printers from around the country. He has been actively engaged as a last wall of defense between the wondrous subtleties of hand-set type and ignominious erasure by the city dump. On the other end of the shop is Robyn’s studio where she turns, saws, and sculpts wood into forms derived from her own imagination and stimulated by the material. Robyn is the famous one of the two, with her works being sold through major galleries throughout the US (see http://robynhorn.com), but the Horn Collection is a partnership. Robyn is the primary decision maker in the acquisitions for the collection. Her curiosity about texture, form and the relationship between these elements of design is a large part of the decision making process about what gets collected.

John deals with the logistics. When not in the print shop, he can be found on the grounds, running a tractor or loader, preparing a foundation for a new sculpture to be added to their collection.

Their home designed by John Connell was finished in 1997 following two and a half years of construction. It was built from the outset to serve as a home for the ever growing and changing collection. John describes it as “a museum with bedrooms.” Its massive stonework, each stone carefully laid to appear dry stacked, anchors the home to the surrounding woods. The large windows and interior height leave little sense of distinction between inside and out, and the carefully arranged collection inside blends seamlessly with large sculptural objects out of doors. The Horn collection consists of over a thousand pieces by over seven hundred artists, and so far has taken 25 years to collect.

Townsend Wolfe, former director of the Arkansas Art Center in Little Rock said of the Horns:

Human beings are collectors---either by accident if we stay in one place too long or on purpose if we discover a particular passion for something. You may have collected something as a child, whether pennies in a collection book or Pokeman trading cards, and you probably noticed that the quality and extent of your collection had to do with two things, your resources and your passion for the process. I collected coins as a kid, carefully going through my father’s pocket money looking for the 1909 SVDB that would have changed my fortune forever. I also filled some of the innumerable blank spaces in my collection books. For some collectors, however, there are no collection books to guide acquisitions. The scope and depth of their collecting is driven by much deeper things, as is the case with Robyn and John Horn.

Robyn and John Horn, live on an acreage called Cedar Glen west of Little Rock. After passing through their gate, you drive through a broad meadow and then enter the glen of cedars that gave the property its name. At times the cedars close in tall and tight on the road, then at points, they move back to provide an expansive view. There are large objects at a distance and others framed close at hand by the forest. Both cause you to pause, arousing your deepest curiosity. “Was that Stonehenge I just passed?” Next you cross a bridge and come to a fork in the road, marked by two stone pillars, joined at the top by a freeform arch. If you turn one way, the road leads through more fields, past a vegetable garden and various large sculptures, up the face of an earthen dam and to the Horn’s home built on the shore of a lake. If you had turned the other way, the road would have taken you winding up through the woods to a large metal building. Meanwhile, back at the fork, the arch at the top of the stone pillars is symbolic. It joins things that might seem divergent, into something unified and whole. If you like, read the arch as symbolic of the lives of John and Robyn, their combined forces brought into a cooperative whole, larger and more meaningful, but it is also symbolic of the joining of two forces in human life, to have, and the other more primal, to make.

Robyn and John Horn, live on an acreage called Cedar Glen west of Little Rock. After passing through their gate, you drive through a broad meadow and then enter the glen of cedars that gave the property its name. At times the cedars close in tall and tight on the road, then at points, they move back to provide an expansive view. There are large objects at a distance and others framed close at hand by the forest. Both cause you to pause, arousing your deepest curiosity. “Was that Stonehenge I just passed?” Next you cross a bridge and come to a fork in the road, marked by two stone pillars, joined at the top by a freeform arch. If you turn one way, the road leads through more fields, past a vegetable garden and various large sculptures, up the face of an earthen dam and to the Horn’s home built on the shore of a lake. If you had turned the other way, the road would have taken you winding up through the woods to a large metal building. Meanwhile, back at the fork, the arch at the top of the stone pillars is symbolic. It joins things that might seem divergent, into something unified and whole. If you like, read the arch as symbolic of the lives of John and Robyn, their combined forces brought into a cooperative whole, larger and more meaningful, but it is also symbolic of the joining of two forces in human life, to have, and the other more primal, to make.John and Robyn Horn have become well known as major collectors. Their collection of American crafts has been featured in American Craft Magazine (Collecting A Life: John and Robyn Horn, Dec. 2000/Jan. 2001). It has also been the subject of an exhibit at the Arkansas Art Center, Living with Form, 2000. Objects from that exhibit are featured in a book, Living with Form, Bradley Publishing 2000. But the objects in the book are the tip of the iceberg in lives dedicated to collecting, and collecting itself can only be understood in light of the ways in which collecting, for the Horns, at least, has been an expression and enhancement of personal creativity and engagement in the arts.

When Robyn and John first met, John was a printer, and Robyn a photographer for Arkansas Parks and Tourism. They collaborated for a time as artists doing stained glass work and selling in craft fairs. The life on the craft show circuit gave John and Robyn a deep sense of appreciation for the challenges faced by artists in marketing their work. In 1984, John’s brother Sam introduced Robyn to woodturning after he returned from a week-long class with David Ellsworth at Arrowmont School of Crafts in Gatlinburg, TN. Robyn took immediately to woodturning and her own creative expression became the driving force in building a collection of works created by others. The richness of texture and form became the foundation for her own search for expression.

In 1990 the Horns bought the property at Cedar Glen and built the metal building that serves as Robyn’s studio and John’s print shop. John, continuing his passion for the printer’s art, has accumulated an incredible collection of antique printing equipment and type from back in the days before ink jets and lasers. It is not an idle collection. He works frequently in the print shop preserving the earlier technology and sharing its subtle creativity with like-minded, obsessed printers from around the country. He has been actively engaged as a last wall of defense between the wondrous subtleties of hand-set type and ignominious erasure by the city dump. On the other end of the shop is Robyn’s studio where she turns, saws, and sculpts wood into forms derived from her own imagination and stimulated by the material. Robyn is the famous one of the two, with her works being sold through major galleries throughout the US (see http://robynhorn.com), but the Horn Collection is a partnership. Robyn is the primary decision maker in the acquisitions for the collection. Her curiosity about texture, form and the relationship between these elements of design is a large part of the decision making process about what gets collected.

John deals with the logistics. When not in the print shop, he can be found on the grounds, running a tractor or loader, preparing a foundation for a new sculpture to be added to their collection.

Their home designed by John Connell was finished in 1997 following two and a half years of construction. It was built from the outset to serve as a home for the ever growing and changing collection. John describes it as “a museum with bedrooms.” Its massive stonework, each stone carefully laid to appear dry stacked, anchors the home to the surrounding woods. The large windows and interior height leave little sense of distinction between inside and out, and the carefully arranged collection inside blends seamlessly with large sculptural objects out of doors. The Horn collection consists of over a thousand pieces by over seven hundred artists, and so far has taken 25 years to collect.

Townsend Wolfe, former director of the Arkansas Art Center in Little Rock said of the Horns:

“John and Robyn Horn are artists and collectors who are committed to every aspect of the contemporary craft movement. They make art themselves, and encourage other artists by acquiring and showing their work. Because of their energy, a whole contemporary craft community s developing and communicating.As stated by Robyn,

The Horns developed their collection in a quiet and consistent manner over the course of years. They did not set out in the beginning to build a collection of crafts, but purchased individual pieces that interest them. Their strong tactile sense of materials and eye for form laid the foundation for seeking out and selecting the objects they acquired.“

“The collector plays an important role in the art world, and the art you choose can enhance your life every time you view it. Painter Eldon Burnicky asked, ‘What is art if it does not awaken one from the mundane?’ It is this awakening that keeps us collecting.”The photo above is sculpture by Robyn Horn. The article is written for an upcoming issue of Ion Arts and will feature photographs from the Horn Collection.

Friday, June 20, 2008

Joe Barry is reading The Gift of Rain by Tan Twan Eng. It is about a boy taught Aikijutsu, the earlier form of Aikido, just before WW II. Joe practiced Aikido almost daily for 20+ years and says he is captivated by the book. He mentions an exchange between the protagonist and his brother as they examine a keris, a traditional Malay blade, and ask:

Joe Barry is reading The Gift of Rain by Tan Twan Eng. It is about a boy taught Aikijutsu, the earlier form of Aikido, just before WW II. Joe practiced Aikido almost daily for 20+ years and says he is captivated by the book. He mentions an exchange between the protagonist and his brother as they examine a keris, a traditional Malay blade, and ask: "Among the creations of our modern world, what do you think will still exist and have historical and aesthetic value five hundred years from now?" (pg 162)As a simple exercise, look through your own possessions in light of what will be here and useful in 500 years. I think perhaps my sloyd knives might make it. If they need new handles, someone, could use one if kept sharp to carve another. In the meantime, I have been busy researching all day, checking libraries and special collections for available materials. Too much time at the keyboard and computer. Those who are able to combine physical activity with their intellectual pursuits are the lucky ones of the modern world. But perhaps even on the keyboard, what we share with others might last and be passed around in human consciousness for 500 years or more. We will never know.

Thursday, June 19, 2008

Today I finished the rustic chair with Danish Oil. Using a spray bottle to apply the oil worked well. I next used compressed air to blow away any excess oil. I may do a final coat of spray polyurethane to seal the wood and bring it to a uniform flat or semi-gloss finish.

In the meantime, I am working on a proposal for a research grant in the field of crafts and it is challenging to state the need for the research in a single page as required:

In the meantime, I am working on a proposal for a research grant in the field of crafts and it is challenging to state the need for the research in a single page as required:

The 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exposition was an important point in the history of crafts education. Featured at the Exposition was the world’s largest Steam engine, a 4 story wonder made by Corliss, that drove over an acre of manufacturing machinery. Also featured were exhibits by two rival systems of woodworking education. What came to be called the “Russian” System was presented by Victor Della Vos of the Moscow Imperial Technical Academy and a smaller display consisting of a series of educational models was presented by a small teacher training school in Nääs, Sweden representing a system of education called by the strange name Educational Sloyd. On the surface there were striking similarities between the two systems, but the first 40 years of technical and craft education in America hinged on a very important debate between the two. The Russian system had the purpose of training workers to take their place in the rapidly evolving industrial economy. Educational Sloyd, whose name was derived from the Swedish word slöjd meaning craft or skilled, on the other hand, aspired toward deeper effect, proposing a broad range of benefits for all children regardless of ultimate academic or career goals.

As described by Industrial Arts Historian Charles A. Bennett, the debate over the two systems was effectively ended in 1916 with the signing of the Smith-Hughes Act by president Woodrow Wilson. The Act provided federal funding for programs designed to prepare workers for industrial employment. It chose to ignore the important educational benefits offered by Educational Sloyd to all students. This act put woodworking and crafts education into the exclusive domain of vocational education while it simultaneously stripped academic education from its responsibility to offer hands-on learning to all students. The intellectual content of hands on learning and education was stripped of stature and recognition, while the important contributions that hands-on learning makes to academic development were shoved from the American educational landscape.

In 2001, concurrent with the start of my woodworking program, Wisdom of the Hands, I began researching Educational Sloyd in my search for historic and theoretical rationale for the use of crafts in general education. While the United States abandoned Sloyd in the period following WWI, Sloyd continued as required curriculum in the Scandinavian countries, currently the world leaders in PISA tests for effective education.

Educational Sloyd, now nearly forgotten in American education, provides a clear rationale for the use of crafts as a major component of general education at all grade levels. Its theoretical foundation, its history, and continued application in Sweden, Finland, Denmark and Norway, should be a major interest among all those concerned with Craft education in America.

A great deal more needs to be done, to research the role of Educational Sloyd in American craft history and share its history and rationale with American educators.

Jed Perl's article on the significance of the human hand in the making of art, The Artisanal Urge can be found on the American Craft Magazine website. It is worth reading.

Wednesday, June 18, 2008

"Where do watermelons come from?" "This time of year, they come from Mexico or Central America." "No, I mean, do they grow underground?" This question was raised by a student in a group of graduating seniors from a major university honors program. The student had scored in excess of 32 on the ACT to qualify for admission and had just finished 4 years of rigorous academic study. Interesting, no?

So what is the point of knowing things that are outside your area of expertise? One of the things that we know now is that the boundaries between disciplines are artificial constructs. There are no clear distinctions between the study of math and the study of art. Physics can be learned and applied in the wood shop. Arts, music and literature are as essential as electrons in the development of technology.

No expertise is useful unless it is deeply and broadly interwoven in a general framework of fundamental reality and human culture.

When I was at the CODA conference, I met with craft school directors and someone mentioned the therapeutic aspect of involvement in crafts. Stuart Rosenfeld of Regional Technologies Strategies, Inc. suggested that we not overlook the way crafts stimulate innovative thinking... His idea was that corporations may be unwilling to invest in craft schools on the basis of therapeutic value, but might be willing to become partners if they were to come to a clear understanding of the ways in which involvement in crafts can stimulate innovation. One of the ways involvement in crafts stimulates innovation is that it breaks down the usual isolation of expertise, bringing in a cross-disciplinary approach to understanding reality.

Of course crafts aren't the only way to reach this important goal. Sometimes sitting on the bank of the river eating watermelon and asking seemingly dumb questions can do the same thing.

So what is the point of knowing things that are outside your area of expertise? One of the things that we know now is that the boundaries between disciplines are artificial constructs. There are no clear distinctions between the study of math and the study of art. Physics can be learned and applied in the wood shop. Arts, music and literature are as essential as electrons in the development of technology.

No expertise is useful unless it is deeply and broadly interwoven in a general framework of fundamental reality and human culture.

When I was at the CODA conference, I met with craft school directors and someone mentioned the therapeutic aspect of involvement in crafts. Stuart Rosenfeld of Regional Technologies Strategies, Inc. suggested that we not overlook the way crafts stimulate innovative thinking... His idea was that corporations may be unwilling to invest in craft schools on the basis of therapeutic value, but might be willing to become partners if they were to come to a clear understanding of the ways in which involvement in crafts can stimulate innovation. One of the ways involvement in crafts stimulates innovation is that it breaks down the usual isolation of expertise, bringing in a cross-disciplinary approach to understanding reality.

Of course crafts aren't the only way to reach this important goal. Sometimes sitting on the bank of the river eating watermelon and asking seemingly dumb questions can do the same thing.

Tuesday, June 17, 2008

This man can move things. It is interesting that scholars have been speculating about this for years. Not surprisingly, Wally is a retired carpenter. More of him doing incredible things with levers and gravity can be found on his website: Forgotten Technology

Monday, June 16, 2008

A review of my speech at the CODA (Craft Organization Development Association) Conference in April is featured in the publication, CraftNet Sketches, June 2008, Vol. 4. CraftNet is an international network of community colleges devising innovative ways through partnerships to develop artisan-based strengths into a sustainable growth sector for each of their service areas. For up-to-date news and information about CraftNet or past issues of CraftNet Sketches, please visit the website of Regional Technology Strategies, Inc. or call 919.933.6699.

Doug Stowe, a self-employed craftsman from Eureka Springs, Arkansas, enchanted his audience with insights gleaned from his experience since 2001 with teaching in a program called “The Wisdom of the Hands” at The Clear Spring School. Stowe and his fellow educators were looking for ways to make woodworking relevant to the lives of all students and meaningful to their broader education. They drew inspiration from an almost forgotten, hands-on pedagogy called “Educational Sloyd” that asks students to use their hands in woodworking projects in order to stimulate their developmental progress in all aspects of academic learning. “Our hands are essential to learning,” Stowe writes in his ongoing blog about his discoveries. “We engage the world and its wonders, sensing and creating primarily through the agency of our hands. We abandon our children to education in boredom and intellectual escapism by failing to engage their hands in learning and making.” For more in-depth discussion about Educational Sloyd and the rewards of integrating hands-on woodworking projects at all levels of youth education, please visit Stowe’s blog.

Doug Stowe, a self-employed craftsman from Eureka Springs, Arkansas, enchanted his audience with insights gleaned from his experience since 2001 with teaching in a program called “The Wisdom of the Hands” at The Clear Spring School. Stowe and his fellow educators were looking for ways to make woodworking relevant to the lives of all students and meaningful to their broader education. They drew inspiration from an almost forgotten, hands-on pedagogy called “Educational Sloyd” that asks students to use their hands in woodworking projects in order to stimulate their developmental progress in all aspects of academic learning. “Our hands are essential to learning,” Stowe writes in his ongoing blog about his discoveries. “We engage the world and its wonders, sensing and creating primarily through the agency of our hands. We abandon our children to education in boredom and intellectual escapism by failing to engage their hands in learning and making.” For more in-depth discussion about Educational Sloyd and the rewards of integrating hands-on woodworking projects at all levels of youth education, please visit Stowe’s blog.

You might enjoy this "digital" clock remembering of course that the word "digit" and "digital" originally referred to the fingers.

dig-it (dij'it), n. [L. digitus, a finger, toe, inch]. 1. a finger or toe. 2. the breadth of a finger, regarded as 3/4 inch. 3. any numeral from 0 to 9: so called because originally counted on fingers. 4. in astronomy, one twelfth the diameter of the sun or moon.

dig-it (dij'it), n. [L. digitus, a finger, toe, inch]. 1. a finger or toe. 2. the breadth of a finger, regarded as 3/4 inch. 3. any numeral from 0 to 9: so called because originally counted on fingers. 4. in astronomy, one twelfth the diameter of the sun or moon.

Saturday, June 14, 2008

Happy Father's Day! I've been reading Wisdom of Our Fathers by Tim Russert, and of course thinking of my own father. I have mentioned him before in the blog, perhaps several times. My earliest easy remembrance of him was when he taught me how to hold a hammer. We were working on a project of some kind in the driveway at 1700 Faxon St. in Memphis, Tennessee. It was an old two story house my mother and father bought and were working continuously, throughout my early childhood to fix up. It took a lot of work, it was hot and humid, and my father was nearly always dripping sweat.

Several homes and years later, we lived in Omaha, Nebraska, and my father came home from work on my 14th birthday with the used Shop Smith I still use today as a drill press and lathe. It is a model 10ER, one of the earliest models. My father, manager of a hardware store at the time, took it in on trade and bought it for the trade-in value of $75.00. He believed that the 10ER was the best machine Shop Smith had made and the fact that it still serves today proves his assessment.

As I grew up in the late 60's I was his helper weekends and summers through high school and summers in college in the hardware store he owned and operated in Valley, Nebraska. It was his encouragement that led me to restore a 1930 model A Ford. As a combat veteran from WWII, he was troubled by my conscientious objector status in the Viet Nam War, but he lived long enough afterwards for us to make peace and for him to see some of my first woodworking projects. As with many WWII vets, he suffered from undiagnosed post traumatic stress disorder. And it really angers me these days to see American servicemen and women put into unconscionable situations for reasons that the best American spin-masters can only explain by lying to the American people. The painful price of war can be passed on for generations, and those who send young men and women to war should know something of what they are sending them into. These things were lessons I learned sitting quietly at night, listening to my father's stories, told reluctantly and only under the liberating influences of alcohol and emotional distress. In the meantime, being a father myself, and reading Tim Russert's wonderful book, I celebrate fatherhood. My father? Perfection he was not, but I was never given cause to doubt his love for me. One day, in spring, he asked me, "Don't you think we should go fishing?" He had been ill from a serious nervous disorder, no doubt resulting from his 299 days of combat, and that kept him from feeling that he was giving me enough as a dad. He voiced that concern on that day as we cast our lines into the water. We loved each other... a point neither of us missed and a thing for which I will always be grateful.

Several homes and years later, we lived in Omaha, Nebraska, and my father came home from work on my 14th birthday with the used Shop Smith I still use today as a drill press and lathe. It is a model 10ER, one of the earliest models. My father, manager of a hardware store at the time, took it in on trade and bought it for the trade-in value of $75.00. He believed that the 10ER was the best machine Shop Smith had made and the fact that it still serves today proves his assessment.

As I grew up in the late 60's I was his helper weekends and summers through high school and summers in college in the hardware store he owned and operated in Valley, Nebraska. It was his encouragement that led me to restore a 1930 model A Ford. As a combat veteran from WWII, he was troubled by my conscientious objector status in the Viet Nam War, but he lived long enough afterwards for us to make peace and for him to see some of my first woodworking projects. As with many WWII vets, he suffered from undiagnosed post traumatic stress disorder. And it really angers me these days to see American servicemen and women put into unconscionable situations for reasons that the best American spin-masters can only explain by lying to the American people. The painful price of war can be passed on for generations, and those who send young men and women to war should know something of what they are sending them into. These things were lessons I learned sitting quietly at night, listening to my father's stories, told reluctantly and only under the liberating influences of alcohol and emotional distress. In the meantime, being a father myself, and reading Tim Russert's wonderful book, I celebrate fatherhood. My father? Perfection he was not, but I was never given cause to doubt his love for me. One day, in spring, he asked me, "Don't you think we should go fishing?" He had been ill from a serious nervous disorder, no doubt resulting from his 299 days of combat, and that kept him from feeling that he was giving me enough as a dad. He voiced that concern on that day as we cast our lines into the water. We loved each other... a point neither of us missed and a thing for which I will always be grateful.

Friday, June 13, 2008

Here are a few photos of student work from a great week at ESSA. I'll be teaching box making there later in the summer.

This is just a bit more from Nicolas Carr's article in Atlantic Monthly. "Is Google Making us Stupid?"

One day I looked up for a moment to see a man in white shirt and tie standing over my shoulder with a clip board in one hand and stop watch in the other. He was timing my actions and watched for a few minutes before he spoke. "You are really going fast, much over quota. How do you do it?" he asked. "I can't stand to be bored," I replied. "Besides, this is my last day." He asked why. So I told him that the other workers had noted that if we worked fast, the management would raise the targets for their performance, but do nothing to improve their pay or working conditions. The result was an oppressive and discordant working atmosphere.

What Taylor failed to understand is the human heart... that the actual distance between two points when observed in human life is never a straight line. We just aren't made for absolute efficiency. The Ancient Chinese, called it "happy wanderings." And happy wanderings are my wish for you this day. If you wander around this blog, use the search function at the top left to search for "rule of thumb." The rule of thumb was the way tools were designed to fit the individual user. If we want a society that fits no one. We can go to Taylor's methods and force conformity. We can even hide the men in the white shirts so we don't even know they are there, watching every move, timing every motion. In the meantime, my small town of Eureka Springs has been described as the town where misfits fit and essentially we are all misfits in one way or another.

Taylor’s tight industrial choreography—his “system,” as he liked to call it—was embraced by manufacturers throughout the country and, in time, around the world. Seeking maximum speed, maximum efficiency, and maximum output, factory owners used time-and-motion studies to organize their work and configure the jobs of their workers. The goal, as Taylor defined it in his celebrated 1911 treatise, The Principles of Scientific Management, was to identify and adopt, for every job, the “one best method” of work and thereby to effect “the gradual substitution of science for rule of thumb throughout the mechanic arts.” Once his system was applied to all acts of manual labor, Taylor assured his followers, it would bring about a restructuring not only of industry but of society, creating a utopia of perfect efficiency. “In the past the man has been first,” he declared; “in the future the system must be first.”This quote brought to mind a time when I was "Taylored." I had been working at a manufacturing company operating a punch press, bending and folding parts to shape for pump oilers. The most important and mindful part of the work was to keep my fingers cleared after the piece of metal was in place and as the mechanism drove down in a whir, crush and wham to force it to shape. The machine was set in motion by a foot pedal, leaving the hands free. I would grab a part from a bin on the left, nest it in place and then be prepared to use my right hand to remove it and throw it into the finished bin. A finger or even a whole hand could disappear in a bloody pulp in a spit second, so there was a mechanical arm that swept across to force your hands clear in case your foot on the pedal got carried away in some ill-timed rhythm of its own. Each set-up was a fascinating execution of mechanical ingenuity and the room was filled with the clacking, crushing cacophony of many similar devices.

Taylor’s system is still very much with us; it remains the ethic of industrial manufacturing. And now, thanks to the growing power that computer engineers and software coders wield over our intellectual lives, Taylor’s ethic is beginning to govern the realm of the mind as well. The Internet is a machine designed for the efficient and automated collection, transmission, and manipulation of information, and its legions of programmers are intent on finding the “one best method”—the perfect algorithm—to carry out every mental movement of what we’ve come to describe as “knowledge work.”

One day I looked up for a moment to see a man in white shirt and tie standing over my shoulder with a clip board in one hand and stop watch in the other. He was timing my actions and watched for a few minutes before he spoke. "You are really going fast, much over quota. How do you do it?" he asked. "I can't stand to be bored," I replied. "Besides, this is my last day." He asked why. So I told him that the other workers had noted that if we worked fast, the management would raise the targets for their performance, but do nothing to improve their pay or working conditions. The result was an oppressive and discordant working atmosphere.

What Taylor failed to understand is the human heart... that the actual distance between two points when observed in human life is never a straight line. We just aren't made for absolute efficiency. The Ancient Chinese, called it "happy wanderings." And happy wanderings are my wish for you this day. If you wander around this blog, use the search function at the top left to search for "rule of thumb." The rule of thumb was the way tools were designed to fit the individual user. If we want a society that fits no one. We can go to Taylor's methods and force conformity. We can even hide the men in the white shirts so we don't even know they are there, watching every move, timing every motion. In the meantime, my small town of Eureka Springs has been described as the town where misfits fit and essentially we are all misfits in one way or another.

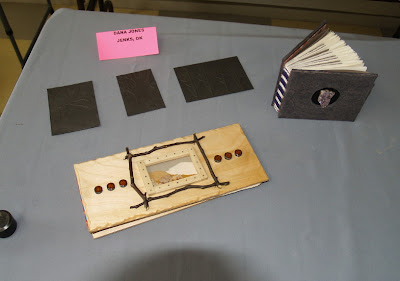

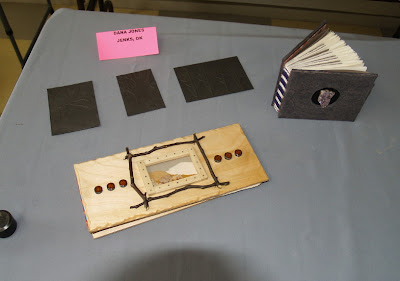

Thursday, June 12, 2008

The photos below are of this week's classes at the Eureka Springs School of the Arts As a board member, I went out to do some volunteer work and to see my friend, teacher Dolph Smith. I'll show more of his work tomorrow. Dolph has some of the smallest woodworking tools I've ever seen, along with an amazing array of interesting materials.He is on e of the artists featured in The Penland Book of Handmade Books. This week's classes are taught by book artist, Dolph Smith, jeweler Judy Carpenter, and metal sculptor Jim Wallace.

Wednesday, June 11, 2008

The following is from an article in the July/August Atlantic Monthly, "Is Google Making us Stupid" by Nicolas Carr.

The following is from an article in the July/August Atlantic Monthly, "Is Google Making us Stupid" by Nicolas Carr.Friedrich Nietzsche was going blind:

The typewriter rescued him, at least for a time. Once he had mastered touch-typing, he was able to write with his eyes closed, using only the tips of his fingers. Words could once again flow from his mind to the page.The case can be made that all tools shape and change the ways we think, just as the hands, as we explore their potentials change the dimensions, range, character and expression of human thought.

But the machine had a subtler effect on his work. One of Nietzsche’s friends, a composer, noticed a change in the style of his writing. His already terse prose had become even tighter, more telegraphic. “Perhaps you will through this instrument even take to a new idiom,” the friend wrote in a letter, noting that, in his own work, his “‘thoughts’ in music and language often depend on the quality of pen and paper.”

“You are right,” Nietzsche replied, “our writing equipment takes part in the forming of our thoughts.” Under the sway of the machine, writes the German media scholar Friedrich A. Kittler, Nietzsche’s prose “changed from arguments to aphorisms, from thoughts to puns, from rhetoric to telegram style.”

Tuesday, June 10, 2008

Joe Barry offered his review written for The Old Saw , the Newsletter of the Guild of New Hampshire Woodworkers to use in the blog and I have chosen to share the first part:

When I began my discussions with wood shop teachers about the fate of woodworking education, as a craftsman myself, I knew that to sit on the sidelines and whine would not lead us toward a solution. So in September 2001 I started the Wisdom of the Hands program at Clear Spring School. In that program I teach kids grades 1-12 using a woodworking curriculum that unites the wood shop with classroom studies in every area of school curriculum. From that experience, I have written woodworking education articles for six different magazines and the Fine Woodworking website.

There is a difference between an academic and a craftsman. The matter has to do with the hands, and the way the hands position a person in direct vs. indirect relation to concrete reality. If your toilet won't flush, do you call a post-doc or a plumber? If you really want to know about craftsmanship, you will need to talk to a craftsman.

The Craftsman. Richard Sennett. Yale University Press. 2008. $27.50.I think Joe and I and many others had high expectations of a book with such a simple but engaging title. Perhaps some disappointment is justified. I was looking forward to the book for the very simple reason that it has been published by Yale University Press and attention to the subjects of skill and craftsmanship by academia is centuries past due. The crafts community is deserving of attention and recognition. I'm doubtful that what we need most will come from academia but from craftsmen themselves. The hands are either the driving force of your intellectual life, or they are not. And they make a difference to your perceptions and subsequent response. A craftsman sees a problem, compares it to direct experience, imagines a possible solution for it, and the next impulse isn't to gather with a group of friends in the student union or library for further discussion leading to mind numbing research proving or disproving the obvious. We, and I'm including you in this, go to our workshops and make. That is essentially why I try to do as much demonstration and visual illustration as possible in the blog. What is an idea that isn't followed by direct action? Empty conjecture. We craftsmen have the unique predisposition to take matters into our own hands.

The crafts revival is over half a century old and has a rich literary tradition. Unfortunately, it would appear that Sociology Professor Richard Sennett is unaware of that that rich tradition. Instead, he lives up to the undergraduate canard about the “fuzzy studies” department in colleges and takes the reader for yet another ride through the thoughts of “dead white men”. The Greeks and the philosophers of the Enlightenment are the core of this rambling and inconclusive book. Rather than the reflective, broad, worldview of contemporary craftsmen that includes the Oriental approaches to craft, Sennett remains firmly rooted to the Eurocentric past.

Instead of a book about the craftsman and his relationship to his tools, materials, and products we get the musings of philosophers who watched work but did not participate except in long scholarly missives. I was reminded of an office sign I was given by one of my ergonomics clients: “I love work. I could sit and watch it all day”.