This blog is dedicated to sharing the concept that our hands are essential to learning- that we engage the world and its wonders, sensing and creating primarily through the agency of our hands. We abandon our children to education in boredom and intellectual escapism by failing to engage their hands in learning and making.

Saturday, September 30, 2006

Independent schools like Clear Spring serve an important function in today's world of education. With public education under increasing stress from legislation like the No Child Left Behind Act, the implementation of new teaching techniques that offer greater engagement in learning and pave the course for the future of all schools is left in the hands of small independent schools like ours.

Clear Spring School has been called "the miracle in the woods." While independent schools generally exist in large market areas where there is a greater demand for private education and where there are well-to-do parents who can afford to give their children the best, Clear Spring School is in a town of barely over 2,000 with the kind of tourist based economy that is well known for low wages and seasonal employment. Survival might be miracle enough under such circumstances, but Clear Spring has grown and developed world class educational programs while sharing the communty's children with a first rate public school system. It has managed to survive and thrive and offer exemplary programs in a poor market due to the passionate involvement of parents, staff and board who take its mission clearly to heart.

"Together, all at the Clear Spring School promote a lifelong love of learning through a hands-on and hearts-engaged educational environment."

You may be at some great distance from our school, but there are ways you may join us and help.

Clear Spring School has been called "the miracle in the woods." While independent schools generally exist in large market areas where there is a greater demand for private education and where there are well-to-do parents who can afford to give their children the best, Clear Spring School is in a town of barely over 2,000 with the kind of tourist based economy that is well known for low wages and seasonal employment. Survival might be miracle enough under such circumstances, but Clear Spring has grown and developed world class educational programs while sharing the communty's children with a first rate public school system. It has managed to survive and thrive and offer exemplary programs in a poor market due to the passionate involvement of parents, staff and board who take its mission clearly to heart.

"Together, all at the Clear Spring School promote a lifelong love of learning through a hands-on and hearts-engaged educational environment."

You may be at some great distance from our school, but there are ways you may join us and help.

Hands-on/Hearts-Engaged at the Clear Spring School

The greatest problems in modern education can be summarized in the 3 D-s… Disengagement, disinterest and disruption. Schools often fail to engage children's innate capacities for learning. In worst cases, students become disruptive of the educational interests and needs of others. At a very early age, children are instructed, "don't touch!" "Keep your hands to yourself!” But the hands and brain comprise an integrated learning/creating system that must be engaged in order to secure the passions and "heart" of our youth. When the passions are engaged and supportive systems (teachers, community resources, technology etc) are in place, students will find no mountain is too high, and no concept too complex to withstand the assault of their sustained interest and attention. There is a rich but near forgotten tradition in America of seeing the integration of head, heart, and hand being essential to the health of the individual and society. The hands-on/hearts-engaged educational strategy at the Clear Spring School is designed to reinforce learning confidence and to enhance a sense of community and social responsibility.

Beginning with pre-primary and extending through high school, Clear Spring School students participate in a multifaceted curriculum that blends reflection and expression, theory and application of ideas derived from direct observation and experimentation, individuality and community responsibility. Instead of re-enforcing the commands “hands-off” and “keep your hands to yourself,” we invite intelligent investigation, cooperative thinking, and creative, useful activity.

Specific programs, depending on grade level, include outdoor education, camping, woodworking, travel school, service learning, mentoring, internships, and interdisciplinary studies.

Outdoor and Environmental Education grades Pre-K though 12

It is essential that our students gain an appreciation for our natural environment, and develop a sense of stewardship and responsibility. Our program of outdoor studies, recycling, camping, and woodworking are all designed to create a greater sense of appreciation and respect for the wonders of our small planet. In addition, all Clear Spring students are actively engaged in recycling and our annual Trash-a-thon Fundraiser.

Camping grades 1 through 6

Our fall and spring camping trips are an adventure in cooperative planning, united effort, group welfare, and outdoor activities. Math, reading, writing, science, cooperative games, outdoor drama local folklore, history, cultural and natural studies are all brought into play.

Woodworking grades 1 through 12

Our nationally recognized woodworking program, the Wisdom of the Hands, is based on an understanding of the importance of the hand/brain learning system that is genetically encoded in each human being. The program is a point of curriculum convergence, where the hands become involved in the studies of math, science, history, design and literature and though which the lessons and experiences from other studies can be directly applied. In addition, as one parent observed, the woodshop is a place the children learn about themselves.

Travel School grades 3 through 12

Through the travel school program, students synthesize learning themes across the curriculum. For example: a week’s journey to the Deep South brings to life through direct experience antebellum architecture, music history, the homes and times of southern writers, US history, economics, as well as native flora, fauna and wildlife. Students complete daily journal assignments, a process which integrates and preserves a record of their observations and experiences. Travel school has been noted to build close, cooperative personal relationships between students, and between students, faculty and volunteer parent chaperones.

Service Learning grades 1 through 12

Service learning takes students into the community to explore real-life community issues and concerns, fostering in the student a sense of greater responsibility and sensitivity. Specific service learning activities include an annual Trash-a-thon (litter pick-up), and recent examples include construction and delivery of walking canes for the elderly, and raising money for hurricane relief. Clear Spring high school students are required to complete 20 hours annually of community service, volunteering with a local organization of their choice. Like internships, service learning encourages students to participate in the life of the local community and lifts the principles of citizenship and civic responsibility off the page and into action.

Student Mentoring grades 7 through 12

Students in the upper grade levels take responsibility as mentors for younger students. These formal and informal interactions are mutually beneficial. Older students learn the value of sharing their time and talents; younger students enjoy the 1:1 attention. We have observed that all students leave these sessions with an air of confidence and satisfaction with themselves.

Learning Through Internships (LTI) grades10 through 12

LTI carries the learning experience beyond the classroom to encompass specialized training and exploratory learning via educational community partnerships, direct on-the-job experiences, group projects, overseen and supervised by daily consultation with school advisors. Students delve into areas of personal interest, explore career possibilities, and establish professional role models. Advisors, students, and internship supervisors develop learning plans to fulfill five areas of requirement: communication, empirical reasoning, personal qualities, quantitative reasoning, and social reasoning.

Integrated Studies all grades

We know that the artificial boundaries constructed between various disciplines create an environment lacking in credibility and creativity. In fact, at the Clear Spring School, we recognize that thinking outside the box involves first and foremost, the ability to interact with information and experience through a multi-disciplinary perspective. We look for every opportunity to explore the boundaries between disciplines for connections that enhance the learning experience.

Block Scheduling

We know that the extremely short time alotted to the exploration of various subjects encourages shallow efforts rather than deep exploration. At the Clear Spring middle school and high school, block scheduling allows greater opportunities for interdisciplinary and multisensory learning experiences and creates greater opportunity for our students to make use of our other hands-on, hearts-engaged program activities.

Most important, the hands-on/hearts-engaged educational strategy is one that has eliminated the 3 D-s from education. Our students and staff at Clear Spring School are 3 E-s...engaged, enthusiastic and eager to learn.

The greatest problems in modern education can be summarized in the 3 D-s… Disengagement, disinterest and disruption. Schools often fail to engage children's innate capacities for learning. In worst cases, students become disruptive of the educational interests and needs of others. At a very early age, children are instructed, "don't touch!" "Keep your hands to yourself!” But the hands and brain comprise an integrated learning/creating system that must be engaged in order to secure the passions and "heart" of our youth. When the passions are engaged and supportive systems (teachers, community resources, technology etc) are in place, students will find no mountain is too high, and no concept too complex to withstand the assault of their sustained interest and attention. There is a rich but near forgotten tradition in America of seeing the integration of head, heart, and hand being essential to the health of the individual and society. The hands-on/hearts-engaged educational strategy at the Clear Spring School is designed to reinforce learning confidence and to enhance a sense of community and social responsibility.

Beginning with pre-primary and extending through high school, Clear Spring School students participate in a multifaceted curriculum that blends reflection and expression, theory and application of ideas derived from direct observation and experimentation, individuality and community responsibility. Instead of re-enforcing the commands “hands-off” and “keep your hands to yourself,” we invite intelligent investigation, cooperative thinking, and creative, useful activity.

Specific programs, depending on grade level, include outdoor education, camping, woodworking, travel school, service learning, mentoring, internships, and interdisciplinary studies.

Outdoor and Environmental Education grades Pre-K though 12

It is essential that our students gain an appreciation for our natural environment, and develop a sense of stewardship and responsibility. Our program of outdoor studies, recycling, camping, and woodworking are all designed to create a greater sense of appreciation and respect for the wonders of our small planet. In addition, all Clear Spring students are actively engaged in recycling and our annual Trash-a-thon Fundraiser.

Camping grades 1 through 6

Our fall and spring camping trips are an adventure in cooperative planning, united effort, group welfare, and outdoor activities. Math, reading, writing, science, cooperative games, outdoor drama local folklore, history, cultural and natural studies are all brought into play.

Woodworking grades 1 through 12

Our nationally recognized woodworking program, the Wisdom of the Hands, is based on an understanding of the importance of the hand/brain learning system that is genetically encoded in each human being. The program is a point of curriculum convergence, where the hands become involved in the studies of math, science, history, design and literature and though which the lessons and experiences from other studies can be directly applied. In addition, as one parent observed, the woodshop is a place the children learn about themselves.

Travel School grades 3 through 12

Through the travel school program, students synthesize learning themes across the curriculum. For example: a week’s journey to the Deep South brings to life through direct experience antebellum architecture, music history, the homes and times of southern writers, US history, economics, as well as native flora, fauna and wildlife. Students complete daily journal assignments, a process which integrates and preserves a record of their observations and experiences. Travel school has been noted to build close, cooperative personal relationships between students, and between students, faculty and volunteer parent chaperones.

Service Learning grades 1 through 12

Service learning takes students into the community to explore real-life community issues and concerns, fostering in the student a sense of greater responsibility and sensitivity. Specific service learning activities include an annual Trash-a-thon (litter pick-up), and recent examples include construction and delivery of walking canes for the elderly, and raising money for hurricane relief. Clear Spring high school students are required to complete 20 hours annually of community service, volunteering with a local organization of their choice. Like internships, service learning encourages students to participate in the life of the local community and lifts the principles of citizenship and civic responsibility off the page and into action.

Student Mentoring grades 7 through 12

Students in the upper grade levels take responsibility as mentors for younger students. These formal and informal interactions are mutually beneficial. Older students learn the value of sharing their time and talents; younger students enjoy the 1:1 attention. We have observed that all students leave these sessions with an air of confidence and satisfaction with themselves.

Learning Through Internships (LTI) grades10 through 12

LTI carries the learning experience beyond the classroom to encompass specialized training and exploratory learning via educational community partnerships, direct on-the-job experiences, group projects, overseen and supervised by daily consultation with school advisors. Students delve into areas of personal interest, explore career possibilities, and establish professional role models. Advisors, students, and internship supervisors develop learning plans to fulfill five areas of requirement: communication, empirical reasoning, personal qualities, quantitative reasoning, and social reasoning.

Integrated Studies all grades

We know that the artificial boundaries constructed between various disciplines create an environment lacking in credibility and creativity. In fact, at the Clear Spring School, we recognize that thinking outside the box involves first and foremost, the ability to interact with information and experience through a multi-disciplinary perspective. We look for every opportunity to explore the boundaries between disciplines for connections that enhance the learning experience.

Block Scheduling

We know that the extremely short time alotted to the exploration of various subjects encourages shallow efforts rather than deep exploration. At the Clear Spring middle school and high school, block scheduling allows greater opportunities for interdisciplinary and multisensory learning experiences and creates greater opportunity for our students to make use of our other hands-on, hearts-engaged program activities.

Most important, the hands-on/hearts-engaged educational strategy is one that has eliminated the 3 D-s from education. Our students and staff at Clear Spring School are 3 E-s...engaged, enthusiastic and eager to learn.

Friday, September 29, 2006

Private and public schools...Their legacy in education...

American President Woodrow Wilson, when president of Princeton University, said the following to the New York City School Teachers Association in 1909: "We want one class of persons to have a liberal education, and we want another class of persons, a very much larger class, of necessity, in every society, to forgo the privileges of a liberal education and fit themselves to perform specific difficult manual tasks."

While few today would buy into such an elitist view of American society, the core of the system of education that arose from such thinking is with us today.

I remember when my mother, a kindergarten teacher would come home from school, surprised and frustrated by the amount of anger and distrust directed by the parents of the children in her classroom toward school. Young fathers would come into her classroom still carrying the load of anger from their own school experiences, and it was my mother's job to win them over, with assurances that their children would be treated with love and respect.

The history of American education is clouded and confused. One the one hand, you have teachers, administrators and parents who have worked hard to lift the level of education to meet its promise. On the other hand, the underlying purposes of those who created the American system of education in the first place, were sinister in light of the commonly held educational values of today.

So the question becomes, how do we transform American education while utilizing the vast long-term commitment and dedication of American teachers? Ron Hansen a professor of teacher education at the University of Western Ontario in Canada has proposed a "diplomatic revolution" in education. While there are many in our country that believe that a revolution is called for and some see no need for diplomacy, the idea of a "diplomatic revolution" is that there are millions of teachers, administrators and parents working each day to make education better in America. Their expertise and commitment is needed; their continuing dedication is required. But efforts made to shore up a system rotten at its core are not enough. Revolution demands that the core, the vision and purpose of education be examined, and built anew.

In the time of Woodrow Wilson, public and private education were opposed parts of a single vision, one controlling the masses, the other preparing the masters for control. It was a dark partnership. Today, there are other things afoot…potentials for partnerships bringing education of all children into greater light. Tomorrow I want to spend a few minutes telling about Clear Spring School.

American President Woodrow Wilson, when president of Princeton University, said the following to the New York City School Teachers Association in 1909: "We want one class of persons to have a liberal education, and we want another class of persons, a very much larger class, of necessity, in every society, to forgo the privileges of a liberal education and fit themselves to perform specific difficult manual tasks."

While few today would buy into such an elitist view of American society, the core of the system of education that arose from such thinking is with us today.

I remember when my mother, a kindergarten teacher would come home from school, surprised and frustrated by the amount of anger and distrust directed by the parents of the children in her classroom toward school. Young fathers would come into her classroom still carrying the load of anger from their own school experiences, and it was my mother's job to win them over, with assurances that their children would be treated with love and respect.

The history of American education is clouded and confused. One the one hand, you have teachers, administrators and parents who have worked hard to lift the level of education to meet its promise. On the other hand, the underlying purposes of those who created the American system of education in the first place, were sinister in light of the commonly held educational values of today.

So the question becomes, how do we transform American education while utilizing the vast long-term commitment and dedication of American teachers? Ron Hansen a professor of teacher education at the University of Western Ontario in Canada has proposed a "diplomatic revolution" in education. While there are many in our country that believe that a revolution is called for and some see no need for diplomacy, the idea of a "diplomatic revolution" is that there are millions of teachers, administrators and parents working each day to make education better in America. Their expertise and commitment is needed; their continuing dedication is required. But efforts made to shore up a system rotten at its core are not enough. Revolution demands that the core, the vision and purpose of education be examined, and built anew.

In the time of Woodrow Wilson, public and private education were opposed parts of a single vision, one controlling the masses, the other preparing the masters for control. It was a dark partnership. Today, there are other things afoot…potentials for partnerships bringing education of all children into greater light. Tomorrow I want to spend a few minutes telling about Clear Spring School.

Thursday, September 28, 2006

Educaton's dirty hidden purpose...We all know that that education has some lofty goals, held in the hearts of many parents and teachers. We think of schools as having the purpose of lifting each child to his or her highest potential and to a life of meaning and fulfillment. But, we also know and seldom acknowledge that schools have other purposes as well, that prevent our loftier goals from having a chance of being fulfilled. If you would like to know a bit about education's dirty hidden purpose, there is a short paper written by John Taylor Gatto that will help you to understand what we are up against. "Against Schools: How public education cripples our kids, and why". I won't ask you to enjoy this paper, but I will ask you to read it. Then let's talk about how to change schools, how to empower our children, and how to become the parents and teachers that our children need and our futures require.

Wednesday, September 27, 2006

There is a great deal of information that points to the significant role of the hands in learning. Anyone who has paid a modicum of attention to observing his or her own learning experience, would know that “hands-on” is the key and won't need experts to tell you what you can see for yourself. But for those who don’t know their hands from a hole in the ground, there are some important things happening that tell us that we have it ALL wrong in most modern classrooms. Some of the research being done in a variety of areas tells us that we have grossly misunderstood the role of the hands in thinking and the development of intelligence.

The first item I’ll point to is the research that concludes that the playing of instrumental music in school has a significant effect on the development of math proficiency. I think it is particularly interesting to consider the role of the hands in the playing of music. It was Frank Wilson’s involvement in music that lead to his book, The Hand: How its use shapes the brain, language and human culture, and while this particular research doesn’t specifically address the hand’s role in learning, instrumental music is clearly hands-on. Was it the music that made the difference, or the use of the hands in playing the music? It would take more extensive research to prove one way or the other. I strongly suspect that both have effect, the music and the hands that play it. The book describing the research can be found for download at The Arts Education Partnership Website. "Critical Links: Learning in the Arts and Student Social and Academic Development," was sponsored by grants from the National Endowment for the Arts and the United States Department of Education and was written by James Catterall, Karen Bradley, Larry Scripp, Terry Baker and Rob Horowitz. It is truly astounding how rarely the United States Government is able to take its own advice. It is a clear case of the left hand not knowing what the right hand is doing.

A second interesting bit of study involves the use of gesture. Susan Goldin-Meadow at the University of Chicago, author of books about the use of gesture, language and intelligence, hypothesizes that the movement of the hands actually facilitates the movement of thought in the brain. One book you might enjoy is Hearing Gesture: How Our Hands Help Us Think

From Susan: “Why must we move our hands when we speak? I suggest that gesturing may help us think - by making it easier to retrieve words, easier to package ideas into words, easier to tie words to the real world. If this is so, gesture may contribute to cognitive growth by easing the learner's cognitive burden and freeing resources for the hard task of learning.

"Moreover, gesture provides an alternate spatial and imagistic route by which ideas can be brought into the learner's cognitive repertoire. That alternative route of expression is less likely to be challenged (or even noticed) than the more explicit and recognized verbal route. Gesture may be more welcoming of fresh ideas than speech and in this way may lead to cognitive change.”

A third interesting bit of research is Baby Signs by Linda Acredolo, Ph.D. and Susan Goodwyn, Ph.D.

Their research into the use of hand signs in communication with toddlers has started a movement among parents wanting to give advantages to their own children. The results of the research show that:

At 24 months, the children taught sign language were on average talking more like 27 or 28 month olds. This represents more than a three-month advantage over the non-signing babies. In addition at 24 months the research subjects were putting together significantly longer sentences.

At 36 months, the children on average were talking like 47 month olds, putting them almost a full year ahead of their average age-mates.

Eight year olds who had been research subjects scored an average of 12 points higher in IQ than their non-signing peers.

It has become very clear that our understanding of the hand/brain system and the role the hands play in learning is far from complete. In the meantime, we are doing harm to our children by requiring them to sit idly at desks with hands stilled.

As a teacher, I have too little time to keep up with all the interesting things happening in the hand world, and I welcome your participation through comments or email to help keep us all informed.

The first item I’ll point to is the research that concludes that the playing of instrumental music in school has a significant effect on the development of math proficiency. I think it is particularly interesting to consider the role of the hands in the playing of music. It was Frank Wilson’s involvement in music that lead to his book, The Hand: How its use shapes the brain, language and human culture, and while this particular research doesn’t specifically address the hand’s role in learning, instrumental music is clearly hands-on. Was it the music that made the difference, or the use of the hands in playing the music? It would take more extensive research to prove one way or the other. I strongly suspect that both have effect, the music and the hands that play it. The book describing the research can be found for download at The Arts Education Partnership Website. "Critical Links: Learning in the Arts and Student Social and Academic Development," was sponsored by grants from the National Endowment for the Arts and the United States Department of Education and was written by James Catterall, Karen Bradley, Larry Scripp, Terry Baker and Rob Horowitz. It is truly astounding how rarely the United States Government is able to take its own advice. It is a clear case of the left hand not knowing what the right hand is doing.

A second interesting bit of study involves the use of gesture. Susan Goldin-Meadow at the University of Chicago, author of books about the use of gesture, language and intelligence, hypothesizes that the movement of the hands actually facilitates the movement of thought in the brain. One book you might enjoy is Hearing Gesture: How Our Hands Help Us Think

From Susan: “Why must we move our hands when we speak? I suggest that gesturing may help us think - by making it easier to retrieve words, easier to package ideas into words, easier to tie words to the real world. If this is so, gesture may contribute to cognitive growth by easing the learner's cognitive burden and freeing resources for the hard task of learning.

"Moreover, gesture provides an alternate spatial and imagistic route by which ideas can be brought into the learner's cognitive repertoire. That alternative route of expression is less likely to be challenged (or even noticed) than the more explicit and recognized verbal route. Gesture may be more welcoming of fresh ideas than speech and in this way may lead to cognitive change.”

A third interesting bit of research is Baby Signs by Linda Acredolo, Ph.D. and Susan Goodwyn, Ph.D.

Their research into the use of hand signs in communication with toddlers has started a movement among parents wanting to give advantages to their own children. The results of the research show that:

At 24 months, the children taught sign language were on average talking more like 27 or 28 month olds. This represents more than a three-month advantage over the non-signing babies. In addition at 24 months the research subjects were putting together significantly longer sentences.

At 36 months, the children on average were talking like 47 month olds, putting them almost a full year ahead of their average age-mates.

Eight year olds who had been research subjects scored an average of 12 points higher in IQ than their non-signing peers.

It has become very clear that our understanding of the hand/brain system and the role the hands play in learning is far from complete. In the meantime, we are doing harm to our children by requiring them to sit idly at desks with hands stilled.

As a teacher, I have too little time to keep up with all the interesting things happening in the hand world, and I welcome your participation through comments or email to help keep us all informed.

The Nature and Art of Workmanship

by David Pye ...

David Pye, UK woodworker, philosopher and author explored the meaning of craftsmanship in his book “the Nature and Art of Workmanship”. The book questions many of the typical assumptions about the values inherent in work and the products of manufacturing and craftsmanship. Pye differentiates between “workmanship of certainty” in which the processes are mechanized, engineered and controlled to achieve a certainty of outcomes and “workmanship of risk” in which the outcome is less predictable and largely dependent on the attention and skill of the craftsman.

This morning as I was brushing my teeth, I couldn’t help but marvel at the simple invention moving through my mouth. It has an ultrasonic vibration that helps to remove microscopic particles, and it cost $3.87 at the local discount store. It is obvious that modern manufacturing is able to offer significant value in the goods made through what David Pye calls workmanship of certainty. If I were to attempt to make a simple toothbrush, I could spend much more than a day doing it, and still not be able to make one myself that would be so effective. Or, I might go outside and with prior knowledge and experience, simply choose something from the range of available natural materials that would suffice, but it would be far less effective than the tooth brush I used this morning.

The age of cheap manufactured goods has called the life of the craftsman or maker into question. It is an old problem, and one that John Ruskin attempted to address long before David Pye. How do we come to an understanding of the value of the handmade object? What are the attributes that give it value? In most circumstances, a handmade object can’t compete with a well-designed manufactured object in either usefulness or price. So where does it compete, and why would someone want to either make or purchase something made by hand?

If you are interested in this question, reading David Pye’s book is a good place to start. Personally, I think the answer lies in an exploration of our own values. If we are a “values damaged” society as suggested by Matti Bergstöm (see post of Thursday, September 14 this blog) and are only able to think of the objects in our lives in the economic terms of supply, demand, price and marginal utility, we might as well forget the hands and all the higher values in human life… things like love, the miracles of growth and the joy of discovery. But if there are other values at work in our lives, we will always have a need to be making things with our own hands and to treasure things made through the inspired hearts and skilled hands of others.

by David Pye ...

David Pye, UK woodworker, philosopher and author explored the meaning of craftsmanship in his book “the Nature and Art of Workmanship”. The book questions many of the typical assumptions about the values inherent in work and the products of manufacturing and craftsmanship. Pye differentiates between “workmanship of certainty” in which the processes are mechanized, engineered and controlled to achieve a certainty of outcomes and “workmanship of risk” in which the outcome is less predictable and largely dependent on the attention and skill of the craftsman.

This morning as I was brushing my teeth, I couldn’t help but marvel at the simple invention moving through my mouth. It has an ultrasonic vibration that helps to remove microscopic particles, and it cost $3.87 at the local discount store. It is obvious that modern manufacturing is able to offer significant value in the goods made through what David Pye calls workmanship of certainty. If I were to attempt to make a simple toothbrush, I could spend much more than a day doing it, and still not be able to make one myself that would be so effective. Or, I might go outside and with prior knowledge and experience, simply choose something from the range of available natural materials that would suffice, but it would be far less effective than the tooth brush I used this morning.

The age of cheap manufactured goods has called the life of the craftsman or maker into question. It is an old problem, and one that John Ruskin attempted to address long before David Pye. How do we come to an understanding of the value of the handmade object? What are the attributes that give it value? In most circumstances, a handmade object can’t compete with a well-designed manufactured object in either usefulness or price. So where does it compete, and why would someone want to either make or purchase something made by hand?

If you are interested in this question, reading David Pye’s book is a good place to start. Personally, I think the answer lies in an exploration of our own values. If we are a “values damaged” society as suggested by Matti Bergstöm (see post of Thursday, September 14 this blog) and are only able to think of the objects in our lives in the economic terms of supply, demand, price and marginal utility, we might as well forget the hands and all the higher values in human life… things like love, the miracles of growth and the joy of discovery. But if there are other values at work in our lives, we will always have a need to be making things with our own hands and to treasure things made through the inspired hearts and skilled hands of others.

Tuesday, September 26, 2006

Step three…painted in a corner; out on a limb… or "where’s a good editor when you need one?"…A few days ago, I promised a simple step-by-step method to turn your life from passive shopper/consumer to one of artist, craftsman, maker. If I had a good editor present in my brain, I would have never made such promises. You may have noticed that steps one and two aren’t easy, and step 3 isn’t either unless you are somewhat tolerant of making a fool of yourself. Step 3 has to do with taking chances. Offering things like this simple step-by-step when you know that you really don’t know where you are going with the dialog except into the corner of your own creativity, and out on a limb where the branch is barely able to support your weight and the only way down is the tiny saw hidden amongst the blades on your Swiss knife..

It is fortunate that blogs really don’t have readers. We bloggers spew things out at an incredible pace, and there can’t possibly be enough readers to keep up with us. So, in effect, I can offer improbable advice, knowing full well that there are no bloggees risking their lives by following my step-by-step mind altering blather.

So step three is to follow my lead. Take chances. There is not an audience sitting in anticipation of watching you fall. If there happens to be one, pretend there isn’t. Art takes its place in the world through the taking of chances, the ignoring of editors, and through bending a few rules.

Tomorrow, Certainty and Risk... the discussions of meaning as suggested by David Pye.

It is fortunate that blogs really don’t have readers. We bloggers spew things out at an incredible pace, and there can’t possibly be enough readers to keep up with us. So, in effect, I can offer improbable advice, knowing full well that there are no bloggees risking their lives by following my step-by-step mind altering blather.

So step three is to follow my lead. Take chances. There is not an audience sitting in anticipation of watching you fall. If there happens to be one, pretend there isn’t. Art takes its place in the world through the taking of chances, the ignoring of editors, and through bending a few rules.

Tomorrow, Certainty and Risk... the discussions of meaning as suggested by David Pye.

Sunday, September 24, 2006

Step two…A friend of mine, Albert, calls the material we engage through the hands, “the working surface”. This is a good concept because it notes that the surfaces we touch through the sensing of the hands, are also shaped by our touch, and possibly refined and made better though our conscious engagement and attention. Albert is a pizza maker, and applies his attention through his hands in the making of dough.

Is dough made with conscious application of mindfulness better than dough made mindlessly and without human care? There are many who would argue on opposing sides of the issue, with some probably believing that the mechanical processing would give more predictable results. Even the hands can be trained to do things mindlessly and without care or attention and get satisfactory results and there are millions of people who prefer squishy white bread. But here we are talking about art, the role of the hands in learning, and the restoration of greater meaning in human life. Greater meaning comes through the application of human attention.

As mentioned yesterday the"homunculus" diagrams illustrate both sensing and motor functions of the hand’s activities in the brain. In fact the hands are the only sensing instruments that also act creatively in human life. In most cases they perform both functions in a trained but unconscious state.

So step two is very much like step one. Restore your attention to the movements of your hands. When you pick up a pencil, pay attention to your grip, and then also pay attention to its movement across the page. When you wash dishes, take childish delight in the warmth of the water and then pay attention to the movement of your hands through it and over the surface of the plates, forks and knives. When you drive the car, consciously lay your fingers onto the wheel and make each movement one of connection and conscious intent. You will reclaim your hands from their unconscious state and liberate your creative consciousness from patterns of destructive thought.

Tomorrow, step three.

Is dough made with conscious application of mindfulness better than dough made mindlessly and without human care? There are many who would argue on opposing sides of the issue, with some probably believing that the mechanical processing would give more predictable results. Even the hands can be trained to do things mindlessly and without care or attention and get satisfactory results and there are millions of people who prefer squishy white bread. But here we are talking about art, the role of the hands in learning, and the restoration of greater meaning in human life. Greater meaning comes through the application of human attention.

As mentioned yesterday the"homunculus" diagrams illustrate both sensing and motor functions of the hand’s activities in the brain. In fact the hands are the only sensing instruments that also act creatively in human life. In most cases they perform both functions in a trained but unconscious state.

So step two is very much like step one. Restore your attention to the movements of your hands. When you pick up a pencil, pay attention to your grip, and then also pay attention to its movement across the page. When you wash dishes, take childish delight in the warmth of the water and then pay attention to the movement of your hands through it and over the surface of the plates, forks and knives. When you drive the car, consciously lay your fingers onto the wheel and make each movement one of connection and conscious intent. You will reclaim your hands from their unconscious state and liberate your creative consciousness from patterns of destructive thought.

Tomorrow, step three.

Saturday, September 23, 2006

Step One...Yesterday, I promised some step-by-step procedure on how to move from the life of the consumer to the life of the craftsman or maker or artist. You may not want to make any changes in your life or you may not see the need. In that case you may be reading the wrong blog.

Every journey starts with the first step, and no skill comes without the direct application of attention and care over a period of time. The first step is actually quite simple and immensely difficult because it involves breaking from a shell composed of intricately woven patterns of thought. Our habits deny attention to the sensitivity of our own hands. We touch things and learn their textures and temperatures, and we use the hands to further refine the information provided by our eyes of their size and shape, but once that information is received, we shut down primary communication with the hands and allow it to be overridden by patterns of circling habitual thoughts from outside the moment.

We can drive hundreds of miles with our hands conforming to the shape of the steering wheel without ever consciously noting their existence and while our thoughts circle in our heads unrelated to the road, to the car, or even to the destination. Essentially, our bodies have become mechanical vessels for the containment of obsessive notions that are most often unrelated to reality and to which we have attached undue importance. All these thoughts swirling in our heads, could actually be useful if we also did things to carry them into action, but generally, we feel things, and even feel them deeply, then congratulate ourselves on the excellent qualities inherent our feelings and then do nothing.

Unused to direct action, and the risk and effort involved, it is far easier and more comfortable for us to simply allow ourselves to become distracted by other desires and the internal dialog related to them. So, we sit on our hands. In fact, our hands have become so well trained to inactivity that sitting on them is no longer necessary.

Days ago, I made reference to "homunculus" diagram published by Penfield and Rasmussen in the 1950 book, The Cerebral Cortex of Man. It illustrates the seemingly disproportionate amount of the cerebral cortex utilized by the human hand. In the diagram, sensing is shown in the drawing at the left, and motor function is shown on the right, illustrating the primal role of the human hand in both the sensing and creating sides of human endeavor.

You can see that the hands have both a sensing function, and a movement or working function. Both of these functions move quickly to the unconscious as the surfaces in which the hands become engaged are known, and the working movements are developed as skilled patterns, no longer requiring direct, conscious attention.

Take the time to notice the hands as they proceed through the exploration of a new object, hold a new tool, or learn a new task. If you are like me, you may notice that in your first time hold on a new object your senses will be acute to the shape, texture and temperature of the object. Then, when you pick up the same object again, and then again, your sensitivity will diminish, becoming unconscious. If the object were to change in some way, you would notice, but not otherwise. Training the motor functions of the hand is often more gradual depending on the complexity and sensitivity of the action required. As an example of a common tool, pick up a pencil or pen. Your prior use of the instrument, the position of it within the hand, its angle in relation to the paper, and its movement across the page, are things learned and practiced throughout your life. At this point in your experience, you can hold a pen or pencil and write with no conscious attention to its presence in your own hand and write with no conscious notice of the movements of the hand.

A step-by-step path to artistic consciousness and growth proceeds as follows: First pay attention to your hands. It is by paying attention that you begin to divert your attention from circling thoughts to the surface of the world you inhabit. First will come a renewed sense of it. Withdraw your attention from the circling thoughts in your mind and place that same attention on the temperature, texture and form of the objects you come in contact with. Whether it is the water used for washing the dishes, or the shape and feel of the steering wheel on your car, the sensory experience of touch can move your experience from the unconscious to the conscious realm, and become the foundation of change in your life.

Tomorrow we will talk about step two.

Every journey starts with the first step, and no skill comes without the direct application of attention and care over a period of time. The first step is actually quite simple and immensely difficult because it involves breaking from a shell composed of intricately woven patterns of thought. Our habits deny attention to the sensitivity of our own hands. We touch things and learn their textures and temperatures, and we use the hands to further refine the information provided by our eyes of their size and shape, but once that information is received, we shut down primary communication with the hands and allow it to be overridden by patterns of circling habitual thoughts from outside the moment.

We can drive hundreds of miles with our hands conforming to the shape of the steering wheel without ever consciously noting their existence and while our thoughts circle in our heads unrelated to the road, to the car, or even to the destination. Essentially, our bodies have become mechanical vessels for the containment of obsessive notions that are most often unrelated to reality and to which we have attached undue importance. All these thoughts swirling in our heads, could actually be useful if we also did things to carry them into action, but generally, we feel things, and even feel them deeply, then congratulate ourselves on the excellent qualities inherent our feelings and then do nothing.

Unused to direct action, and the risk and effort involved, it is far easier and more comfortable for us to simply allow ourselves to become distracted by other desires and the internal dialog related to them. So, we sit on our hands. In fact, our hands have become so well trained to inactivity that sitting on them is no longer necessary.

Days ago, I made reference to "homunculus" diagram published by Penfield and Rasmussen in the 1950 book, The Cerebral Cortex of Man. It illustrates the seemingly disproportionate amount of the cerebral cortex utilized by the human hand. In the diagram, sensing is shown in the drawing at the left, and motor function is shown on the right, illustrating the primal role of the human hand in both the sensing and creating sides of human endeavor.

You can see that the hands have both a sensing function, and a movement or working function. Both of these functions move quickly to the unconscious as the surfaces in which the hands become engaged are known, and the working movements are developed as skilled patterns, no longer requiring direct, conscious attention.

Take the time to notice the hands as they proceed through the exploration of a new object, hold a new tool, or learn a new task. If you are like me, you may notice that in your first time hold on a new object your senses will be acute to the shape, texture and temperature of the object. Then, when you pick up the same object again, and then again, your sensitivity will diminish, becoming unconscious. If the object were to change in some way, you would notice, but not otherwise. Training the motor functions of the hand is often more gradual depending on the complexity and sensitivity of the action required. As an example of a common tool, pick up a pencil or pen. Your prior use of the instrument, the position of it within the hand, its angle in relation to the paper, and its movement across the page, are things learned and practiced throughout your life. At this point in your experience, you can hold a pen or pencil and write with no conscious attention to its presence in your own hand and write with no conscious notice of the movements of the hand.

A step-by-step path to artistic consciousness and growth proceeds as follows: First pay attention to your hands. It is by paying attention that you begin to divert your attention from circling thoughts to the surface of the world you inhabit. First will come a renewed sense of it. Withdraw your attention from the circling thoughts in your mind and place that same attention on the temperature, texture and form of the objects you come in contact with. Whether it is the water used for washing the dishes, or the shape and feel of the steering wheel on your car, the sensory experience of touch can move your experience from the unconscious to the conscious realm, and become the foundation of change in your life.

Tomorrow we will talk about step two.

Friday, September 22, 2006

Sawdust Therapy...…Many woodworkers call their time in the woodshop, "sawdust therapy" in recognition of the kinds of feelings they get from it. A woodshop can be an escape from the pressures of the world. We can go into our workshops and feel rejuvenated and empowered. We can fall into creative activities that wisp us away into mental states in which time passes unnoticed and from which we emerge refreshed.

I particularly notice the effect when I’ve been away from the shop for some time. I take the first piece of wood and pass one edge across the jointer in preparation to start a project. An immediate sense of wellbeing comes over me. I've learned in conversations with other woodworkers and those involved in other hands-on activities, whether in the studio, the garden or the kitchen, that their feelings are the same.

We live with so many things in this world that we can't control, with each having such huge impact on our lives. Time in the woodshop, making something that requires our loving attention can take our minds off things we can do nothing about and places it squarely on things that we can control.

Move a gouge into the turning stock on a lathe, and you will observe the change in shape of the wood and the stream of shavings that fly from the cutting edge. Move a plane down the length of a board and you watch the ribbon of wood emerge from the mouth of the plane and then feel the straight smooth edge that results from your labor. Even something as simple as moving a piece of sand paper along the surface of a board, leaves noticeable effect, changing the state of the wood from coarse to smooth and at the same time having a similar effect on the mental and emotional state of the craftsman. Sometimes the effects are small, and you will need to pay careful attention but they are cumulative and will have affect.

It is interesting that one of the primary symptoms of depression is the sense of loss of control in one's own life. You can feel like things are spinning away on their own unrelated to your own input or control. With this in mind, you can see how a woodworker might call it "therapy."

If you watch carefully, and are engaged in observations of your own hands at work, you will see that a "feedback loop" is in effect. Can you see how this direct feedback loop can be used as a counter to the devastating symptoms of depression?

It is interesting that many people deal with depressive episodes by shopping. To go into a store and get feedback in the form of attention and acknowledgement from a clerk, and then to go out and be noticed by friends wearing your most recent acquisitions can shift attitudes, as long as you can afford the costs, the extensive time involved in shopping and are shallow enough to think that the attentions of the sales clerk are earned by something other that the available credit line on your charge card. As a contrast, imagine the feedback you can get in the making of an object; first in your own feelings of growth and success, and then in sharing it with others? Can you see a difference between attention bought and attention earned?

Check your credit line and the depth of your character to see the limits of the one course of action. Look to your imagination, and your willingness to put your time and attention in the practice of an art for the other. As a craftsman, I mourn for those who don't know the difference.

It is amazing how easy it is to see things and understand things, and how difficult it can be to actually turn the tide of one's life from empty consumerism to fulfillment of one's life and potentials in the arts. Please tune in tomorrow for the simple step-by-step.

I particularly notice the effect when I’ve been away from the shop for some time. I take the first piece of wood and pass one edge across the jointer in preparation to start a project. An immediate sense of wellbeing comes over me. I've learned in conversations with other woodworkers and those involved in other hands-on activities, whether in the studio, the garden or the kitchen, that their feelings are the same.

We live with so many things in this world that we can't control, with each having such huge impact on our lives. Time in the woodshop, making something that requires our loving attention can take our minds off things we can do nothing about and places it squarely on things that we can control.

Move a gouge into the turning stock on a lathe, and you will observe the change in shape of the wood and the stream of shavings that fly from the cutting edge. Move a plane down the length of a board and you watch the ribbon of wood emerge from the mouth of the plane and then feel the straight smooth edge that results from your labor. Even something as simple as moving a piece of sand paper along the surface of a board, leaves noticeable effect, changing the state of the wood from coarse to smooth and at the same time having a similar effect on the mental and emotional state of the craftsman. Sometimes the effects are small, and you will need to pay careful attention but they are cumulative and will have affect.

It is interesting that one of the primary symptoms of depression is the sense of loss of control in one's own life. You can feel like things are spinning away on their own unrelated to your own input or control. With this in mind, you can see how a woodworker might call it "therapy."

If you watch carefully, and are engaged in observations of your own hands at work, you will see that a "feedback loop" is in effect. Can you see how this direct feedback loop can be used as a counter to the devastating symptoms of depression?

It is interesting that many people deal with depressive episodes by shopping. To go into a store and get feedback in the form of attention and acknowledgement from a clerk, and then to go out and be noticed by friends wearing your most recent acquisitions can shift attitudes, as long as you can afford the costs, the extensive time involved in shopping and are shallow enough to think that the attentions of the sales clerk are earned by something other that the available credit line on your charge card. As a contrast, imagine the feedback you can get in the making of an object; first in your own feelings of growth and success, and then in sharing it with others? Can you see a difference between attention bought and attention earned?

Check your credit line and the depth of your character to see the limits of the one course of action. Look to your imagination, and your willingness to put your time and attention in the practice of an art for the other. As a craftsman, I mourn for those who don't know the difference.

It is amazing how easy it is to see things and understand things, and how difficult it can be to actually turn the tide of one's life from empty consumerism to fulfillment of one's life and potentials in the arts. Please tune in tomorrow for the simple step-by-step.

Tuesday, September 19, 2006

What in the world are we doing? While technology hurls us headlong into a proposed glorious (or dubious) future, the actual human organism advances at a snail's pace. The evolutionary changes in the human organism are such that if one of us were to be directly compared with one of our ancestors of over 10,000 years ago, very little difference could be found. The structures within the brain would be the same.

Life has always been experimental. Failed experiments fall to the wayside, while the fundamental organism trods on through time. At no time, however has life been more experimental, and some of us have concerns about the risks we present to our children. Scientific experiments usually try to control certain variables so that the implications of other variables can be determined and understood. As we hurtle head-on into our technological age, there are no fixed variables to help us to predict or even understand our fate. The education of our children is perhaps the least scientific of all our endeavors, and perhaps the area in which our culture is most at risk.

My old college economics professor said that the real cost of something isn't the money spent on it, but what you have given up in order to have it. The real costs of our computer driven educational model isn't the amount of money being spent on it but that we have allowed it to take the place of other kinds of time tested and proven processes through which hand-brain learning has systematically developed human intelligence.

When I was a child, my hands were always busy manipulating a wide variety of materials, digging in the earth, folding paper, braiding string, yarn and hair, hammering and sawing, and in the place of these diverse manipulations, we have substituted the keyboard. None who have had the chance to see a young man or woman of today using a keyboard will doubt that they too, are engaged with the world through their hands. But, there is a difference. The keys are designed to be free of texture, and temperature neutral to prevent obstruction of input into the digital process. In gaming, motions are purposely a-rhythmic, requiring what some have described as twitch mechanism to gain success. This is quite unlike the varied textures and the rhythmic and soothing hand motions one would find in braiding or various forms of textile work, or other crafts. And as any woodworker or student of woodworking or of any other craft can tell, to have tangible, tactile, hold-in-your-hands and touch consequences to your actions is to commune and connect with the miraculous. The digital world can't come close.

There is a saying in woodworking, that if the only tool you have is a hammer, all the world's challenges look like nails. The current situation is that while the computer can be a wonderful and effective tool, we have placed it in our children's hands to the absolute and certain neglect of all the other tools from which our culture was derived. If the computer is the only tool our children have, will they begin to see all the world's problems as issues to be resolved through a change in data entry? We already live in an age of media spin in which facts are twisted and retold in ways to shape our opinions contrary to the hands-on common sense we might have acquired with real tools working with the actual substance of the material world. The message of modern times is this: If you don't like the way things are, don't change them. Lie about them over and over until you get someone to believe you and then maybe you will even start to believe them yourself. And yet, there is still a real world out there, and those with hands, brains and hearts can discover things.

The image above is a stone hammer used by native Americans. Found in gardening our front yard, it had been shaped by hand to fit the hand and was probably used in the grinding of small seeds and nuts and perhaps in the softening of hides. It was only by holding in my own hand that its use could be discovered.

Life has always been experimental. Failed experiments fall to the wayside, while the fundamental organism trods on through time. At no time, however has life been more experimental, and some of us have concerns about the risks we present to our children. Scientific experiments usually try to control certain variables so that the implications of other variables can be determined and understood. As we hurtle head-on into our technological age, there are no fixed variables to help us to predict or even understand our fate. The education of our children is perhaps the least scientific of all our endeavors, and perhaps the area in which our culture is most at risk.

My old college economics professor said that the real cost of something isn't the money spent on it, but what you have given up in order to have it. The real costs of our computer driven educational model isn't the amount of money being spent on it but that we have allowed it to take the place of other kinds of time tested and proven processes through which hand-brain learning has systematically developed human intelligence.

When I was a child, my hands were always busy manipulating a wide variety of materials, digging in the earth, folding paper, braiding string, yarn and hair, hammering and sawing, and in the place of these diverse manipulations, we have substituted the keyboard. None who have had the chance to see a young man or woman of today using a keyboard will doubt that they too, are engaged with the world through their hands. But, there is a difference. The keys are designed to be free of texture, and temperature neutral to prevent obstruction of input into the digital process. In gaming, motions are purposely a-rhythmic, requiring what some have described as twitch mechanism to gain success. This is quite unlike the varied textures and the rhythmic and soothing hand motions one would find in braiding or various forms of textile work, or other crafts. And as any woodworker or student of woodworking or of any other craft can tell, to have tangible, tactile, hold-in-your-hands and touch consequences to your actions is to commune and connect with the miraculous. The digital world can't come close.

There is a saying in woodworking, that if the only tool you have is a hammer, all the world's challenges look like nails. The current situation is that while the computer can be a wonderful and effective tool, we have placed it in our children's hands to the absolute and certain neglect of all the other tools from which our culture was derived. If the computer is the only tool our children have, will they begin to see all the world's problems as issues to be resolved through a change in data entry? We already live in an age of media spin in which facts are twisted and retold in ways to shape our opinions contrary to the hands-on common sense we might have acquired with real tools working with the actual substance of the material world. The message of modern times is this: If you don't like the way things are, don't change them. Lie about them over and over until you get someone to believe you and then maybe you will even start to believe them yourself. And yet, there is still a real world out there, and those with hands, brains and hearts can discover things.

The image above is a stone hammer used by native Americans. Found in gardening our front yard, it had been shaped by hand to fit the hand and was probably used in the grinding of small seeds and nuts and perhaps in the softening of hides. It was only by holding in my own hand that its use could be discovered.

Monday, September 18, 2006

Canes and T-squares...One of the best things about teaching woodshop is the opportunity to be creatively engaged in work with children. There are literally thousands of things that can be made from wood that can connect children with their communities or deepen the educational experience. I've found that as my confidence has grown, my imagination has grown also, and it has become quite easy to come up with projects that integrate and support nearly every field of study. I've placed a couple example projects on my website today, making them available for download as pdf files. You are welcome to use these projects in your own classroom, or with your own children in the woodshop. The canes were made as a public service project with seventh and eighth grades. The students enjoyed the project so much that some decided to make canes for themselves as well. "I plan to be old someday," one student said.

The T-squares were made with a 9th grade class prior to a unit in drafting. I wanted them to make their own tools that they could take home with them, enabling the students to carry the experience and skills acquired away from the classroom.

The T-squares were made with a 9th grade class prior to a unit in drafting. I wanted them to make their own tools that they could take home with them, enabling the students to carry the experience and skills acquired away from the classroom.

Sunday, September 17, 2006

Mora in May. We arrived in Mora on prom night after a long drive from Nääs. Mora is an industrial city at the heart of Sweden. After finding a hotel, my traveling companion Jim and I went out for a walk and noticed that there were scores of old American cars from the 50's, 60's and 70's, in varying degrees of restoration, from pristine to works in progress. The one that impressed us the most was a Chevelle from the early 60's with a 396 engine and slicks. We first heard the very loud and prolonged screaming of tires on pavement, and then were blanketed in a thick, acrid cloud of burned rubber.

When we told new friends in Nääs that we would be driving first to Mora and then to my conference in Umeå, they were somewhat incredulous. It would take so long, they said. Evidently the great American roadtrip is uncommon in Sweden where gas prices are about $7.00 a gallon.

On the way to Mora, we drove through beautiful countryside, largely unihabited forest and lake shore. When we found "loppis" or "Loppamarknad" (flea market) advertised in the small towns, we stopped to look for antique Sloyd knives. Of course the ones I found and bought were marked Mora, as that was the city in which they were traditionally made, and where they are still made today. So, our journey with Sloyd at its heart through the heartlands of Sweden was made more complete by our arrival in Mora, a small city on the shores of one of Europe's largest meteor crater lakes.

We asked at the hotel, about the surprising number of old American cars. One hotel clerk explained that it was prom night and that instead of renting limosines as in the US, they ride around in old American cars. Another clerk explained that in the darkness of the long winter nights, the people have to have something to do, so for many, fixing up old American cars is a passion. They fix them and then the first nice weekend after the ice melts on the lake, they drive. For some, like the young man with the Chevelle, the driving is wild. My last view of his car was headed down the highway with the hands of his companions holding their vodka bottles out the windows on both sides.

Prior to the industrial revolution, when Sweden was primarily a farming country, men and women sat by the fire on long winter nights crafting things that were both useful and beautiful in which they took great pride, and which provided a source of revenue from their local communities. The industrial revolution changed a few things. The abundance of cheap but well made consumer goods eliminated the market for the hand-crafted goods that were previously bartered among friends. So, the farmers, bored with long winter nights learned to make Vodka. Does this sound like a fairy tale? Perhaps by Brothers Grimm?

You can see this same scenario played out in third world countries today. There are things that happen to people when the value of their heritage is lost, and when the deeper values of their own work are obscured. In fact, you can find the same phenomenon here in Arkansas where lives are destroyed by alcohol and meth.

There is a saying that using firewood to heat your home warms you twice. First there is the warmth (you might call it sweat) that comes from cutting and splitting, and then there is the warmth that comes from burning it in your stove.

Making something from wood serves you twice, first in the making as you discover your creative power, and then when the object takes its place of usefulness and beauty in your home. When you have become experienced in the making and know the feelings of empowerment that come from your own creativity, you will know that the making is even better than the having. To give up our role as makers to become mere consumers of an endless chain of meaningless objects is tragic. It could drive you to the desperation of making your own Vodka.

But, things can be changed and made right. Make sure your children get to spend some time with scissors, knives, hammers, saws, wood, clay, or even cardboard. Have tools available so they can take things apart when they break and learn how things work and maybe fix them. It may ultimately serve them better than struggling for an extra point on the ACT. We are beginning to understand the role of the hands in the development of intelligence, and your children with the right tools and understanding may surpass the dreams you have for them.

When we told new friends in Nääs that we would be driving first to Mora and then to my conference in Umeå, they were somewhat incredulous. It would take so long, they said. Evidently the great American roadtrip is uncommon in Sweden where gas prices are about $7.00 a gallon.

On the way to Mora, we drove through beautiful countryside, largely unihabited forest and lake shore. When we found "loppis" or "Loppamarknad" (flea market) advertised in the small towns, we stopped to look for antique Sloyd knives. Of course the ones I found and bought were marked Mora, as that was the city in which they were traditionally made, and where they are still made today. So, our journey with Sloyd at its heart through the heartlands of Sweden was made more complete by our arrival in Mora, a small city on the shores of one of Europe's largest meteor crater lakes.

We asked at the hotel, about the surprising number of old American cars. One hotel clerk explained that it was prom night and that instead of renting limosines as in the US, they ride around in old American cars. Another clerk explained that in the darkness of the long winter nights, the people have to have something to do, so for many, fixing up old American cars is a passion. They fix them and then the first nice weekend after the ice melts on the lake, they drive. For some, like the young man with the Chevelle, the driving is wild. My last view of his car was headed down the highway with the hands of his companions holding their vodka bottles out the windows on both sides.

Prior to the industrial revolution, when Sweden was primarily a farming country, men and women sat by the fire on long winter nights crafting things that were both useful and beautiful in which they took great pride, and which provided a source of revenue from their local communities. The industrial revolution changed a few things. The abundance of cheap but well made consumer goods eliminated the market for the hand-crafted goods that were previously bartered among friends. So, the farmers, bored with long winter nights learned to make Vodka. Does this sound like a fairy tale? Perhaps by Brothers Grimm?

You can see this same scenario played out in third world countries today. There are things that happen to people when the value of their heritage is lost, and when the deeper values of their own work are obscured. In fact, you can find the same phenomenon here in Arkansas where lives are destroyed by alcohol and meth.

There is a saying that using firewood to heat your home warms you twice. First there is the warmth (you might call it sweat) that comes from cutting and splitting, and then there is the warmth that comes from burning it in your stove.

Making something from wood serves you twice, first in the making as you discover your creative power, and then when the object takes its place of usefulness and beauty in your home. When you have become experienced in the making and know the feelings of empowerment that come from your own creativity, you will know that the making is even better than the having. To give up our role as makers to become mere consumers of an endless chain of meaningless objects is tragic. It could drive you to the desperation of making your own Vodka.

But, things can be changed and made right. Make sure your children get to spend some time with scissors, knives, hammers, saws, wood, clay, or even cardboard. Have tools available so they can take things apart when they break and learn how things work and maybe fix them. It may ultimately serve them better than struggling for an extra point on the ACT. We are beginning to understand the role of the hands in the development of intelligence, and your children with the right tools and understanding may surpass the dreams you have for them.

Saturday, September 16, 2006

Sloyd in Wikipedia.org

I have been busy posting an entry in the Wikipedia on-line encyclopedia about Sloyd. My sister Sue read the blog and noted that while she knew a bit about Sloyd, very few people in the whole country that didn't know me, or hadn't read my articles in Woodwork Magazine would know the least thing about it.

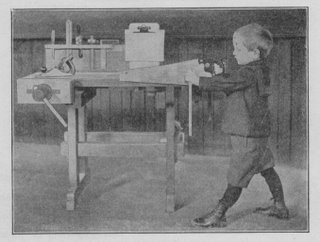

Over the next weeks or months, if you hang around, you will learn quite a bit about about Sloyd and perhaps even learn how to use it in the modern classroom. If you would like to know a bit more now please read the article at Wikipedia.org. The photo above is from an early Sloyd text.

I have been busy posting an entry in the Wikipedia on-line encyclopedia about Sloyd. My sister Sue read the blog and noted that while she knew a bit about Sloyd, very few people in the whole country that didn't know me, or hadn't read my articles in Woodwork Magazine would know the least thing about it.

Over the next weeks or months, if you hang around, you will learn quite a bit about about Sloyd and perhaps even learn how to use it in the modern classroom. If you would like to know a bit more now please read the article at Wikipedia.org. The photo above is from an early Sloyd text.

Friday, September 15, 2006

Narrative qualities of work...Many craft artists consider their work to be narrative, meaning it tells a story. Some use words inscribed in the work to connect it with a particular episode or important principle in their lives. But all craft work is narrative in that it records the artist's understanding of the material, his or her level of skill, and much more. Of course it also records the hours involved in the making of the work, and the years involved in the development of skill. A particular piece of work may record a moment of discovery, or a point of arrival at a new plateau both in the life of the artist or in the whole of human culture. Great museums are full of objects whose significance is not their beauty alone, but the stories that they've recorded and tell of human history.

The photo above is the tine or cheesebox that my great grandmother carried from Norway as a young woman of 11 in 1865. In it she carried her prized personal possessions. It was a simpler time. Imagine a child of today trying to decide which of his or her things were significant enough to fill the limited space within a small box. When my mother was a child, her grandmother's tine was where the family photos were kept. Then during my childhood, the box was empty, and yet it was treasured as a connection with family heritage.

It is not perfect workmanship, and that it exists over a hundred and fifty years after it was made, perhaps tells more about my family and love shared through generations than it does about its maker. The latches were broken off and are missing. A crack through the lid was fixed at some point with nails. The red milk paint turned brown very long ago. It exists at this point because people through generations made decisions about its significance, then sheltered it, repaired it, dusted it, and kept it in a place of honor.